The hydropower segment finally received some policy attention this year with the central government introducing initiatives to revive the industry. The segment has long faced challenges such as stranded projects, limited offtakers, lack of finance and high tariffs. To reduce the stress in the segment, the union cabinet, in March 2019, approved a slew of measures including the much-awaited renewable energy status for all hydroelectric projects (HEPs), the introduction of a hydro purchase obligation (HPO), tariff rationalisation and increased budgetary support. The measures are indeed a step in the right direction and are expected to revive investor interest in the sector. That said, challenges arising due to delays in environmental clearances continue to impede project implementation.

Capacity addition

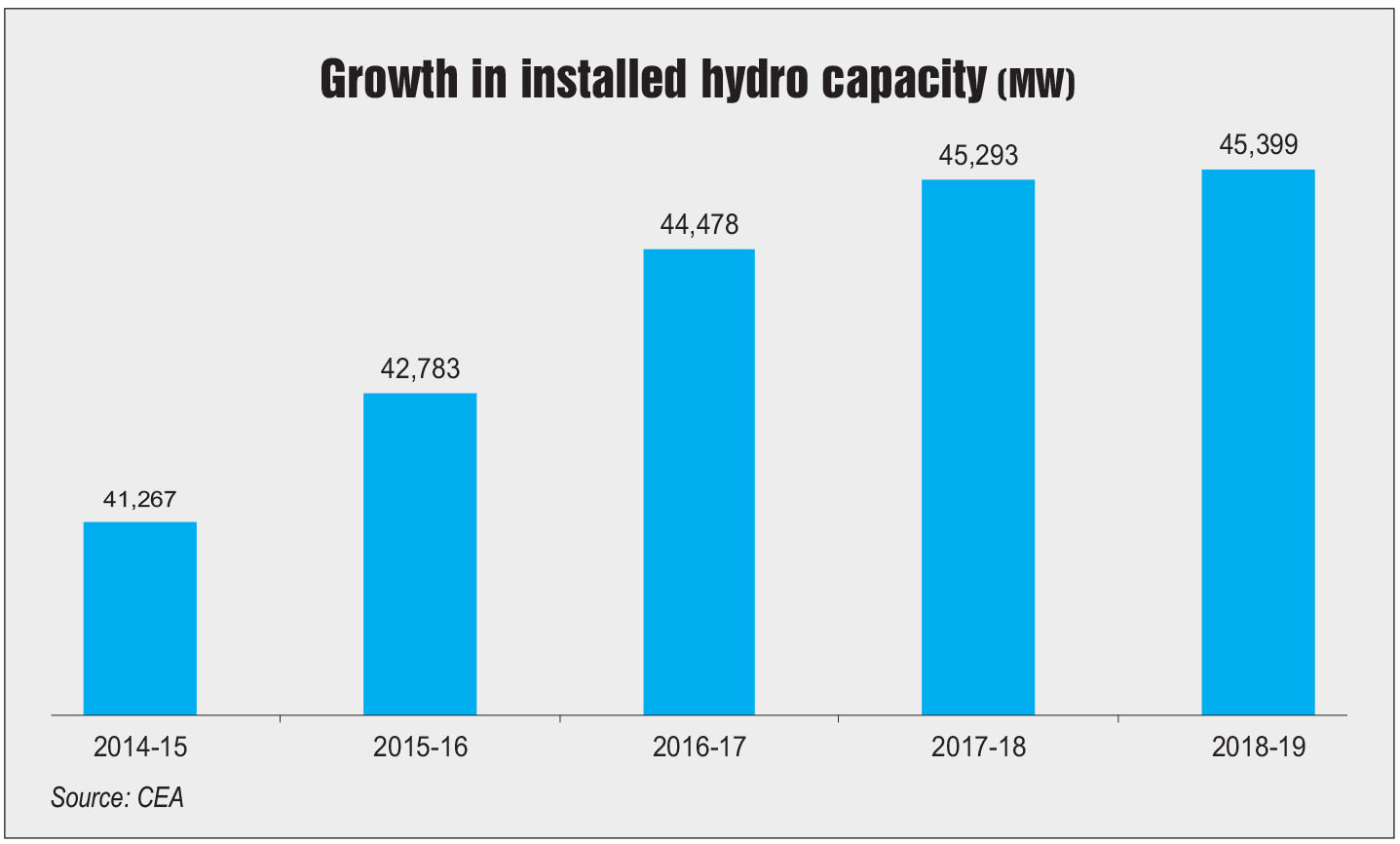

The country’s installed hydropower capacity stood at 45,399.22 MW as of June 2019. It grew at a compound annual growth rate of about 2.4 per cent between 2014-15 and 2018-19; in comparison, coal-based capacity grew at 5 per cent and renewable energy capacity at nearly 19 per cent during this period. The annual hydropower capacity additions have also remained low. The year 2018-19 recorded the lowest capacity addition in the past five years at just 140 MW. No project has been commissioned in 2019-20 as of July 2019.

In terms of generation, hydropower plants produced 135,039 MUs of electricity in 2018-19, an increase of 7 per cent over the 126,123 MUs generated in the previous year. However, the share of hydropower in the overall generation mix has reduced over the years. It declined from 12 per cent in 2014-15 to 10 per cent in 2018-19. This is largely due to the increase in renewable power generation. The share of renewables increased from 6 per cent to 8 per cent during the same period. In addition, erratic monsoons and a decrease in the flow of rivers have contributed to lower generation.

Stranded projects

As of February 2019, there were 13 stalled HEPs in the country with a total capacity of 4,706 MW. These projects entail a total anticipated investment of Rs 525 billion, of which Rs 246 billion has already been undertaken. These projects are likely to be commissioned in one to five years, depending on the current stage of the project. Some of the key stalled projects are NHPC’s 2,000 MW Subansiri Lower HEP entailing an anticipated investment of Rs 194 billion (Rs 104 billion already undertaken), the 500 MW Teesta Stage VI HEP entailing an investment of Rs 75.42 billion (Rs 36.21 billion already invested) and GVK’s 850 MW Ratle HEP entailing an investment of Rs 62.75 billion (Rs 14.51 billion invested). The Teesta Stage VI HEP was to be developed by Lanco Infratech but was acquired by NHPC as part of the former’s insolvency proceedings. The cabinet approved the investment for the acquisition and execution of balance work by NHPC in March 2019.

Some of the key reasons for slippages in time and cost are geological, hydrological and topological constraints and surprises. Apart from this, delays in environmental clearances are a key challenge.

Eight of the 13 stalled HEPs are facing financial constraints. Apart from this, two HEPs are facing regulatory and legal hurdles while another two HEPs are stalled due to opposition from local authorities, activists, etc., and one is stalled because of a dispute with the contractor.

Measures to promote hydro

The most important step taken by the Ministry of Power is the declaration of all hydro projects as renewables. Previously, only small-hydro projects fell under the ambit of renewable energy. Notably, hydropower projects are categorised as renewables in all countries. Their inclusion in the renewable energy sector will provide HEPs access to the subsidies and benefits available to renewable projects thereby bringing hydropower and renewables, both of which are green and clean sources of energy, on the same level. For instance, benefits such as waiver of interstate transmission charges, must-run status, and accelerated depreciation benefit will promote investments in the segment. That said, given the sustainability concerns, large hydro projects will continue to require statutory clearances (forest and environmental clearances, related impact assessments, etc.), which are exempted for small-hydro projects (of up to 25 MW capacity).

Further, HPOs will be identified as a separate entity within the non-solar renewable purchase obligation (RPO). This means, the state distribution utilities will have to meet a certain proportion of their total power requirement through hydropower. This will facilitate the signing of power purchase agreements and enable the financial closure of hydro projects. However, it must be noted that RPOs as a policy instrument have not succeeded due to lack of compliance, which creates uncertainty about the future of HPOs too. In the past nine years, 27 states and union territories in India have achieved less than 60 per cent of their RPOs. Further, HPOs will be applicable only to hydropower projects commissioned after March 8, 2019, and currently, no under-construction HEP is close to completion.

Tariff rationalisation measures have also been approved for hydropower projects. The debt repayment period has been increased from 12 years to 18 years and project life from 35 years to 40 years. The government has also allowed a 2 per cent escalation in hydropower tariffs, which is subject to approval of the appropriate regulatory commissions. This will increase the viability of projects and make them more competitive by backloading the debt repayment requirements and lowering the regulated tariff in the initial years. The implementation of these measures will depend on subsequent amendments to the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission tariff regulations. Further, it remains to be seen how financial institutions will look at this when evaluating the financing terms and conditions, and ensure that project developers’ return on investment in the initial operating period is not impacted.

Further, budgetary support for the flood moderation component and infrastructure (roads, bridges, etc.) of HEPs will be provided on a case-by-case basis. Thus, these costs will be excluded from tariff determination, making hydropower tariffs more competitive. This will incentivise hydropower’s multi-purpose use and help in realising its associated benefits related to flood control, drought mitigation, irrigation, etc. It will also aid the development of projects that are remotely located. The amount of funds to be released will be decided on a case-by-case basis, following the appraisal of each project by the Public Investment Board or the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs. The upper limit of the grant has been set at Rs 15 million per MW for projects up to 200 MW, and at Rs 10 million per MW for projects above 200 MW. It may be noted that the development of enabling infrastructure requires significant upfront investment and thus more clarity on this is needed. It will be useful if a part of such payment is released before the construction stage.

Issues and challenges

The development of HEPs is more complex and time consuming than that of conventional fossil fuel-based projects and renewable energy projects. HEPs can take 5-13 years for completion while coal-based power plants can be set up in four to five years and renewable energy projects may be completed in just a few months. The capital cost of hydropower projects is also significantly higher. As per estimates, the cost of HEPs works out over Rs 100 million per MW vis-à-vis Rs 60-65 million for solar projects and Rs 70-75 million for coal-based plants. Owing to the high capital cost, the initial tariff for recently commissioned HEPs is considerably higher leading to offtake issues. For instance, the composite tariff for NHPC’s Chutak HEP stood at Rs 8.26 per unit and for Nimmo Bazgo it was Rs 9.24 per unit for 2018-19.

Further, HEPs face challenges related to land acquisition, environmental and forest approvals, and resettlement and rehabilitation of locals, which results in time and cost overruns. Other issues pertain to provisions like free supply of power to the host state, the absence of long-term power procurement bids by discoms, and the lack of skilled engineering, procurement and construction contractors.

Essentially, the entire value chain of the hydropower segment is fraught with risks, making these projects financially unviable. As a result, private investment in the sector lags behind others such as thermal and renewables. The share of private players in the installed hydropower capacity is only 7 per cent vis-à-vis 40 per cent in thermal and 95 per cent in wind and solar.

Project pipeline

As of March 2019, hydropower projects aggregating 12,034.5 MW were under construction in the country including 1,205 MW of hydro pumped storage capacity. Of this, 7,215 MW was installed by the central sector, 2,337.50 MW by the state sector, and 2,482 MW by the private sector. These projects are expected to be commissioned by 2023-24 (subject to restart of work in the case of stalled projects). In addition, the government approved Rs 42.87 billion in investment for the construction of the Kiru hydro project (624 MW) in March 2019. The project will be implemented by Chenab Valley Power Projects Private Limited, a joint venture of NHPC, Jammu and Kashmir State Power Development Corporation Limited and PTC India Limited with an equity shareholding of 49 per cent, 49 per cent and 2 per cent respectively. It is scheduled for completion in four and a half years. Further, the role of pumped storage plants (PSPs) is expected to increase in the coming years with greater integration of renewable energy as they can act as energy reservoirs to balance load. Currently, the installed capacity of PSPs in the country stands at 4,786 MW across nine PSPs. Meanwhile, three PSPs aggregating 1,205 MW are under construction – THDC India’s 1,000 MW Tehri PSP in Uttarakhand, TANGEDCO’s 125 MW Kundah Pump Storage Phase I, and the 80 MW Koyna Left Bank by Maharashtra State Power Generation Company Limited. Further, the detailed project report for the 1,000 MW Turga PSP in West Bengal has been approved by the Central Electricity Authority of India. Three PSPs aggregating 2,920 MW are also under survey and investigation.

Future outlook

The recent measures notified by the government to promote the hydropower segment are indeed positive, especially as they come after years of policy inaction. However, they are not enough. The revival of the segment requires concerted efforts involving the participation of the central and state governments as well as local authorities to resolve the issues of under-construction projects on a case-by-case basis. For promoting new investments in the segment, the government could adopt the plug-and-play model as followed in Case 2 bidding for new hydropower projects, wherein clearances and approvals are already in place.

Going forward, greater investments and more concrete measures will be needed given the significance of HEPs in balancing the load and meeting peaking power requirements.