The installed capacity of rooftop solar systems in India increased from an almost negligible amount in 2012 to 525 MW by October 2015. Driven by the decline in solar panel costs and the operational success of established projects, the central government has decided to promote rooftop solar generation on a large scale. Of the 100 GW solar capacity it is targeting by 2022, 40 GW is to be contributed by rooftop plants. While policy intent at the central and state levels has been supportive, a major growth driver for the segment has been the decreasing cost of solar generation. Rooftop solar has already achieved grid parity for commercial and industrial consumers in states like Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Delhi and Odisha.

The other factor that is expected to fuel large-scale capacity addition in the rooftop segment, especially among residential consumers, is net metering. This mechanism allows consumers to generate and consume solar power within their premises and feed excess generation into the grid. The consumers then pay only for the net imported energy. Net metering is a direct, inexpensive and easily administered mechanism for encouraging customers to install small-scale renewable energy facilities on their buildings. It also allows a rooftop solar system’s excess power to be fed into the grid, which can be used to offset electricity consumption in future billing cycles.

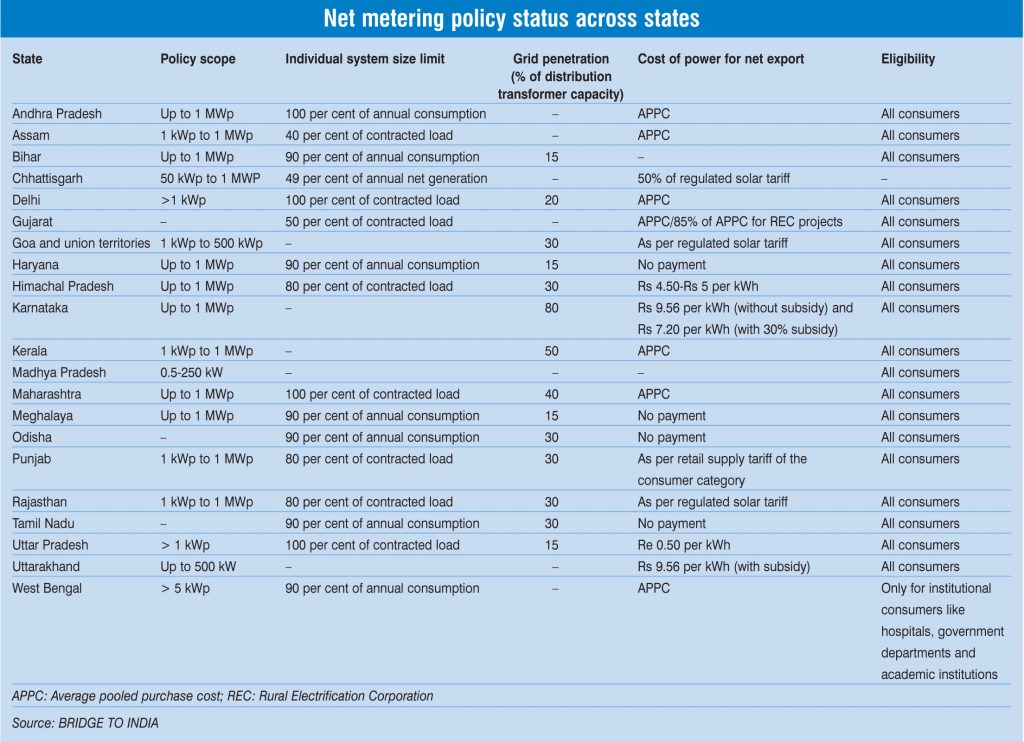

In India, about 21 states have issued their respective net metering regulations (see table), with varying stipulations regarding each parameter. For instance, most states have a capacity limitation of 90 per cent of the annual consumption of customers and/or 10 per cent of the peak capacity for a particular distribution transformer. Though this is considered important for maintaining grid operations, such a ruling could affect the adoption of rooftop solar technology in the near term. Most state regulations also do not specify whether the energy generated from a net metering-based rooftop solar system will be eligible to be part of the renewable energy certificate mechanism. Moreover, while Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan pay consumers for excess generation, Tamil Nadu and Haryana have no such rule in place.

Despite the obvious gains, the net metering arrangement has its own set of challenges as well. The primary issue relates to the awareness of regulations and policies at the local level. While many state governments have announced net metering guidelines, they have not done enough to educate local utility officials and the general public about how they should be implemented.

Another major concern is that the grid is not stable in most parts of India. For net metering to work effectively, the grid should be stable and available at all times. Since there aren’t any inverters that can flip the power to be used by a household at the time of load shedding, the consumer has to bear generation loss during such events. This raises a key question regarding the use of batteries in a net metering-based rooftop solar system. If the system architecture allows the power generated at the time of load shedding to be stored in a battery, power loss can be avoided. However, most of the regulations released so far do not address this issue. Another hindrance is that the installation of a net meter is the prerogative of consumers in almost all state regulations, adding to their costs.

Thus, efforts are being made by state and central regulators to establish a strong net metering mechanism but certain missing links in the value chain can restrict the uptake of rooftop solar projects. Generating awareness and laying out clear policies and directives are imperative for creating a robust net metering framework.