In recent months, coal availability at thermal power plants (TPPs) in the country has been under pressure owing to an interplay of various factors. These include evacuation constraints, a sudden increase in coal demand and a shortfall in coal production owing to heavy rains. TPPs’ coal stocks plummeted to 11 days on August 1, 2018. Meanwhile, coal imports grew to 208 million tonnes (mt) in 2017-18 after three years of a steady decline till 2016-17. The shortage will continue over the next three years while new mines are geared up to start production. In the interim, the shortfall in supply is likely to be met through imports. Amidst these developments, changes in power sector dynamics are raising concerns over the future of coal. Developments such as India’s climate commitments and the rapid development of renewable energy sources are expected to impact the demand for coal in the long term. A look at the key trends, developments and outlook for the coal market in India…

Key trends

In the first five months of 2017-18 (April to August), the total coal production from Coal India Limited (CIL) and Singareni Collieries Company Limited (SCCL) stood at 273 mt, marking an increase of 8.8 per cent year on year. Coal offtake during the same period stood at 240 mt, marking a year on year increase of 10.7 per cent. Meanwhile, during the period 2013-14 to 2017-18, the coal production from CIL and SCCL grew at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.25 per cent. Between 2012-13 and 2016-17, the total coal demand grew at a CAGR of 3.4 per cent to reach 885 mt. While the demand for non-coking coal grew at 3.5 per cent, that for coking coal grew at 2 per cent. For 2017-18, the Ministry of Coal (MoC) has estimated a coal demand of 908 mt – 845 mt for non-coking coal and 63 mt for coking coal.

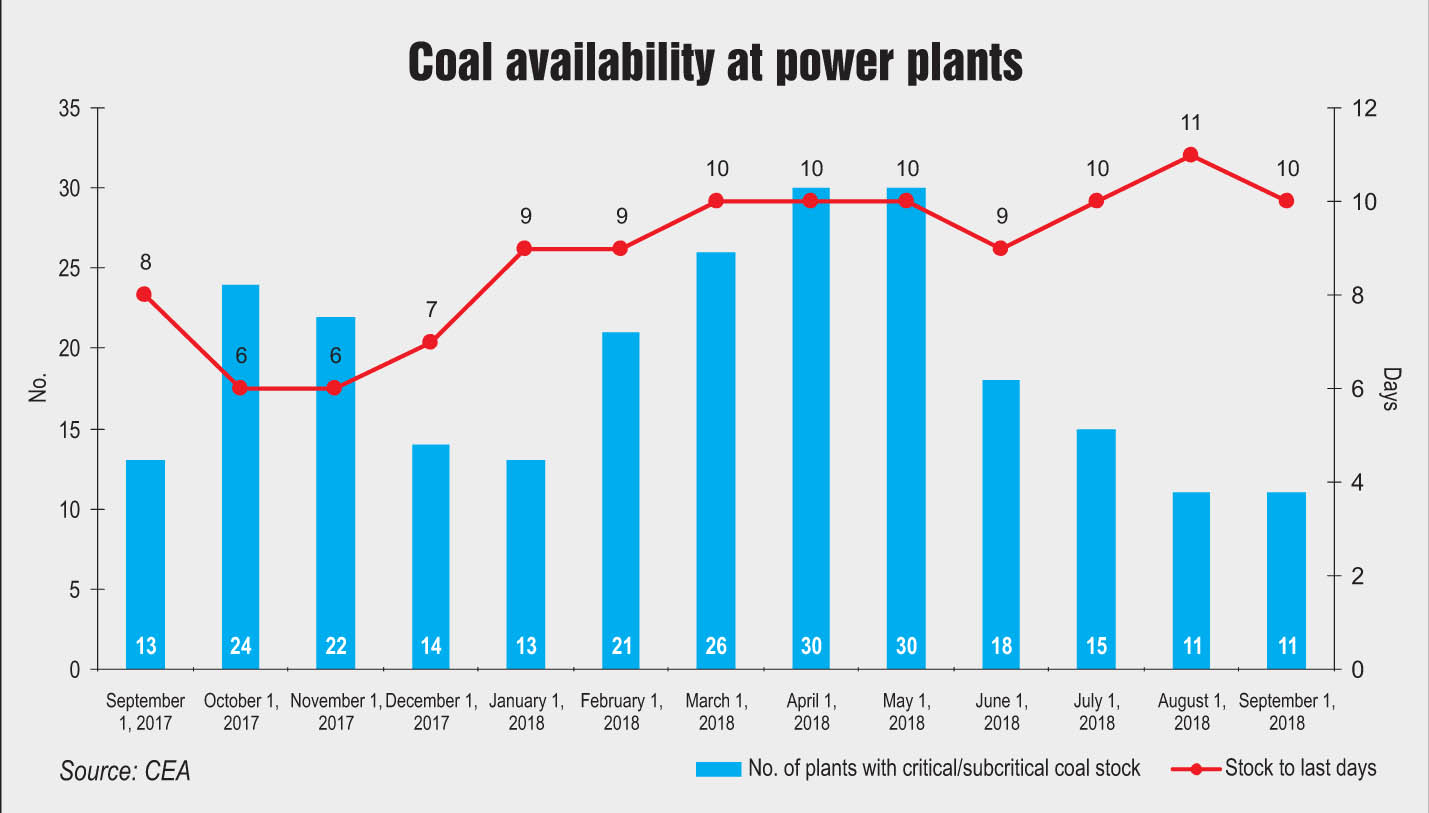

With regard to coal imports, in 2018-19 (up to June 2018), the power sector imported 14 per cent less coal than that in the corresponding period last year. Meanwhile, between 2013-14 and 2017-18, total coal imports grew at a CAGR of 6.3 per cent to reach 208 mt.On a year-on-year basis, coal imports witnessed an increase of 9.5 per cent during 2017-18. With regard to the coal stocks available at TPPs, during the past one year (as on the first of every month) the plants had coal stocks of around six days (October-November 2017) and 11 days (August 2018). The number of power plants with critical/subcritical coal stock ranged from 11 (August–September 2018) to 30 plants (April-May 2018). In order to meet the shortfall in coal supply, developers are participating in spot auctions, which witnessed coal prices of Rs 2,966 per tonne in August 2018.

Current coal scenario

Current coal scenario

As against the coal surplus scenario witnessed in early 2017, the coal availability at power plants has been under pressure during the past 12-14 months. In the last couple of months, coal shortages have occurred primarily because of a decline in coal output from certain mines owing to flooding and heavy rains as well as an increase in coal demand. Hydro generation during April and May 2018 failed to meet the target, and the shortfall was met through increased thermal generation. With regard to the coal shortages faced during September-October 2017, the primary reason was the lack of rack availability and transportation constraints. Following the glut in coal production in early 2017, the mismanagement of coal evacuation and the lack of sufficient coal at plants to meet demand fluctuations led to shortages in coal availability.

The recent coal shortages are a bellwether of the power cuts likely to be experienced in the coming months. The latest news reports suggest that the northern states are vulnerable to power cuts owing to disruptions in fuel supply to 4,200 MW of generation capacity. Meanwhile, Tamil Nadu is facing a shortfall in power supply from 1,410 MW of capacity, owing to coal shortages. Besides this, generation from NTPC’s Farakka and Kahalgaon TPPs has been lowered to 60 per cent and 80 per cent respectively from around 90 per cent a couple of months ago, owing to a decline in coal output from the Rajmahal mines in Jharkhand because of depleting reserves. In order to tackle coal shortages and prevent repercussions, the Ministry of Power had written to the states in July 2018, notifying them about the coal shortage issue and asking them to import coal to meet demand. Besides this, NTPC is planning to import 2.5 mt of coal, which would be utilised at its coastal power projects such as Simhadri, Kudgi and Farakka. The company had last imported coal three years ago, and is now expected to shell out Rs 13.72 billion at $80 per tonne of coal to meet its planned coal imports.

Recent developments

On the policy front, one of the key recent developments has been the release of a policy for the rationalisation of coal linkages to independent power producers (IPP). An IPP can procure coal from a company other than the one with which it has signed the contract by swapping its coal linkage with that of another IPP with closer mines. This flexibility in coal linkage is expected to yield significant savings and ensure lower coal transportation costs for power plants. With regard to commercial coal mining, the ministry has recently put its plan on hold, owing to pressure from the trade unions of state-run coal companies. In February 2018, the ministry had announced plans to roll out the reform and had identified nine mines initially for the purpose. Meanwhile, of the 204 captive coal blocks cancelled in 2014, 25 blocks have so far been allocated through the auction route while 58 coal blocks have been allocated to public sector companies through the allotment route. The last two rounds of coal block auctions were cancelled, owing to the lack of participation. The government has since been mulling over relaxing the conditions regarding the minimum number of bidders, incorporating an exit clause and allowing lower coal production than full capacity, among other things, in the tender document.

With regard to coal pricing, in January 2018, CIL notified an increase of up to 22 per cent in the prices of coal grades between G6 and G14. While grades G8 to G10 witnessed a marginal increase of 3-5 per cent, grades G6 to G7 and G11 to G14 witnessed an increase of 13-22 per cent. The increase in SCCL’s coal prices has been similar to that of CIL. Apart from this, in January 2018, CIL had announced a new pricing policy, which involves selling coal on the basis of the total energy content in each consignment. However, the methodology has attracted criticism from some sections for not accounting for moisture content in the calculation. Notwithstanding this, the new pricing policy, once implemented, is likely to resolve the issues of coal quality and grade slippage in coal bills.

Future coal demand

For better management of coal demand and supply, CIL had engaged KPMG as a consultant to assess the future demand scenario. “Coal Vision 2030”, the draft document prepared by KPMG, notes that coal demand in the country would continue to grow until 2030, though at a CAGR of 3 per cent vis-a-vis the 6 per cent witnessed in the past five years. It estimates the overall coal demand to be 900–1,000 mtpa by 2020 and 1,300–1,900 mtpa by 2030. As against the earlier scenario, wherein energy demand was met almost entirely by coal, the demand for coal as a fuel is now undergoing a change. This is primarily owing to the growing influx of renewable energy and a change in the environmental and regulatory regimes. However, given the crucial role that coal-based power plays in grid balancing as well as the large installed coal capacity in the country, the demand for coal as a fuel is here to stay. In order to ensure efficient power generation and lower the level of harmful emissions, TPPs are increasingly moving towards the use of washed coal and supercritical technologies, as well as renovation and modernisation of inefficient and old power plants.

Coal supply outlook

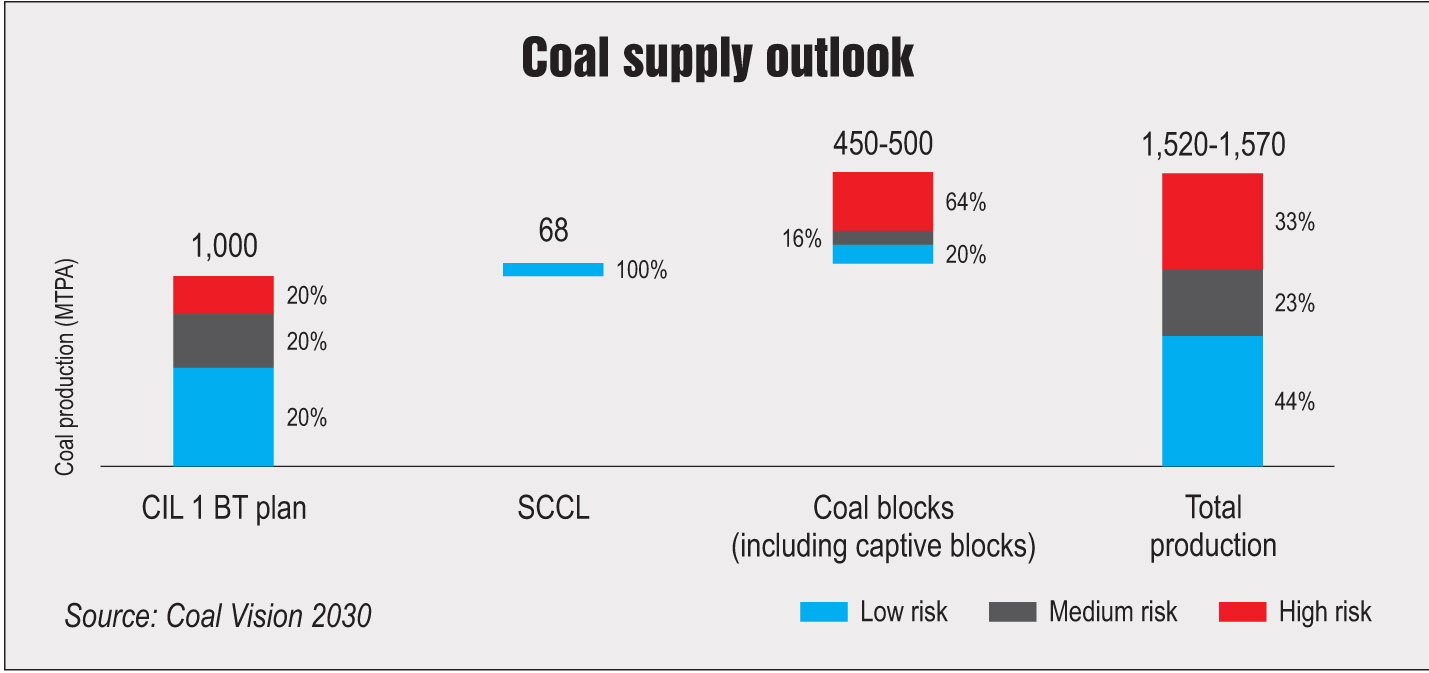

In line with the recommendations made in the Coal Vision 2030, CIL has revised its production targets and aims to achieve a coal production of 928.77 billion tonnes (bt) by 2025-26 and 1,135 bt by 2030-31, as against 1 bt by 2019-20. The vision document proposes that there is a limited requirement to start new coal mines, and only those that have been already auctioned/allocated need to be developed for meeting coal demand in the coming years. In the short term, however, coal production is likely to be significantly lower than the potential since the majority of the mines currently auctioned/allocated are scheduled to be completed by 2019-20. Further, owing to delayed clearances, land acquisition problems, rehabilitation and resettlement issues, and evacuation constraints, 33 per cent of the capacity is at the risk of delay. Hence, the estimated coal production in the short term (2020–22) is 1,050 mtpa, which is comparable to the demand.

Conclusion

Conclusion

The government has taken a number of steps to manage coal shortages, such as improving the transportation network for coal, issuing an advisory to the state governments to import coal and introducing coal linkage rationalisation. While these initiatives have provided some relief, it is only when the upcoming coal mines begin production that the coal demand can be met from domestic sources.

Priyanka Kwatra