The Indian automobile industry is on the cusp of transitioning to electric vehicles (EVs) from internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles over the course of the next decade. This transition is being driven by the alignment of demand-side, supply-side and technological growth drivers such as declining costs of batteries (66 per cent reduction in nine years), governmental policy support for indigenous manufacturing of advanced batteries worth $2.4 billion by way of the production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme and the Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Hybrid and EV (FAME) II scheme for the development of charging infrastructure alongside demand-side policies.

However, key barriers relating to EV adoption, pertaining to technology costs, infrastructure availability and consumer behaviour, need to be overcome. Incentives that reduce the upfront cost of EVs, such as the FAME II incentive, are a critical first-order solution. Although less commonly discussed, financing – in terms of the cost and the quantum of capital – is another hurdle for India’s electric mobility transition.

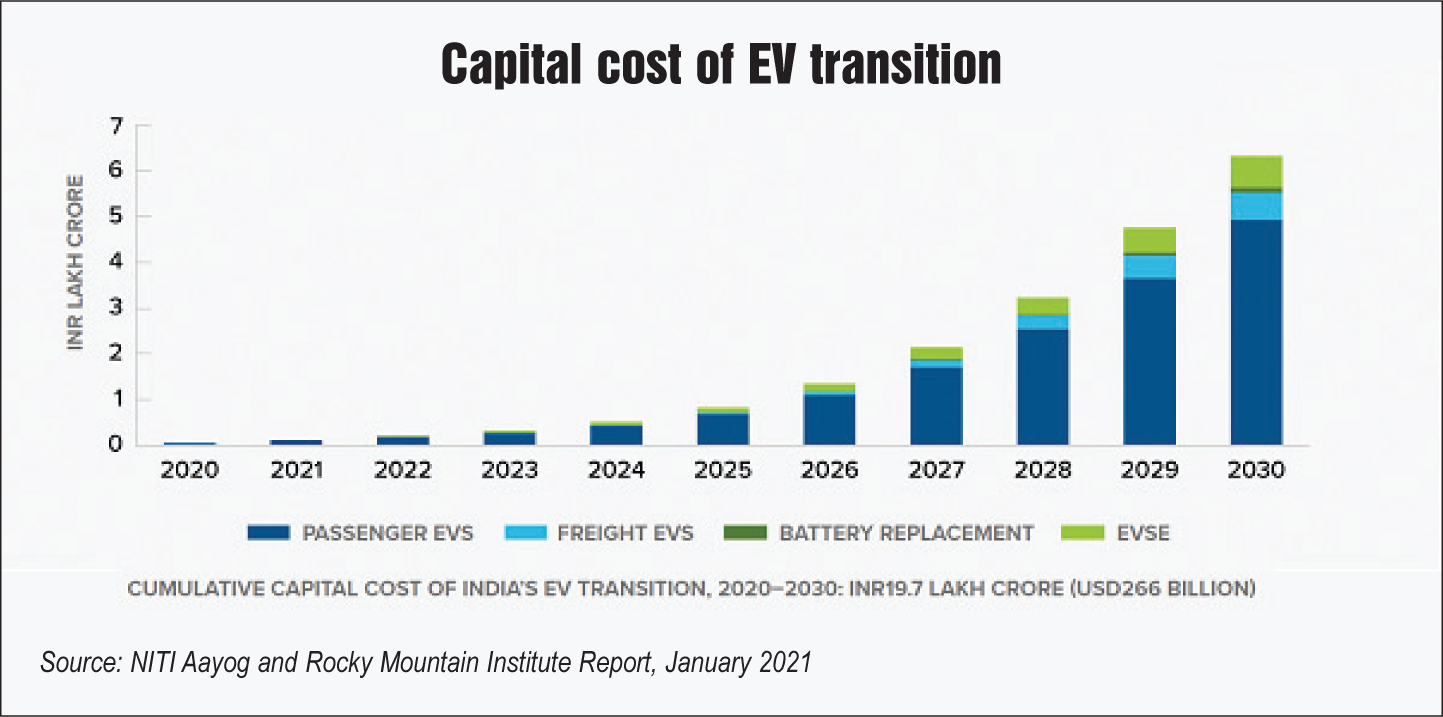

Highlighting the importance of mobilising finances, a new report by NITI Aayog and Rocky Mountain Institute titled “Mobilising Finance for EVs in India: A Toolkit of Solutions to Mitigate Risks and Address Market Barriers” has identified solutions to direct capital and financing to aid in India’s EV transition. As per its estimates, India requires a cumulative capital expenditure of Rs 19.7 trillion on battery infrastructure, EV supply equipment and vehicles over the next decade in order to enable the transformation towards electric mobility across all segments. The estimated size of the annual loan market for EVs would be Rs 3,700 billion in 2030.

Current EV landscape

At the central level, a number of interventions are being implemented. The central government has reduced the goods and services tax on EVs sold with batteries from 12 per cent to 5 per cent, in addition to the introduction of FAME I with demand incentives of Rs 9.7 billion and FAME II with an outlay of Rs 100 billion, with the objective of commissioning a robust battery ecosystem and charging infrastructure sufficient to spur the mass adoption of EVs. The Ministry of Road Transport and Highways exempted EVs from permit requirements and recommended that states reduce or waive road taxes for EVs.

In addition, the National Mission on Transformative Mobility and Battery Storage was approved in March 2019. Its goal is to increase domestic battery manufacturing and accelerate the adoption of e-mobility. Moreover, the central government has also approved a PLI scheme worth Rs 181 billion to encourage advanced chemistry cell production.

At the state level, as of January 2021, 10 states have developed EV policies, while six states are still in the process of drafting a policy. There are some states such as Maharashtra and Karnataka, that have designed a policy framework intending to boost EV original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) as well by offering financial benefits to battery/component manufacturers in their states, in order to ensure the development of manufacturing clusters in their state.

EV financing scenario

EV financing scenario

High financing cost and uncertainty around long-term economics – including resale value – remain both real and perceived issues for financial institutions. There are risks associated with the nascent electric mobility ecosystem. They have given rise to problems such as high interest and insurance rates, low loan-to-value ratio and limited financing options for retail customers. This may lead to unsecured borrowing from the unorganised sector at even higher rates. Further, both vehicle financing and EV sectors are diverse. Levels of total cost of ownership (TCO) parity and incentive structures available for each segment, use case and stakeholder are different. Private electric two-wheelers, for example, would have vastly different parameters to consider in financing, compared to e-buses used for public transport. This creates the need for government, industry and financial institutions to collaborate on a set of customised EV financing solutions. It also creates a role for OEM-owned financial companies to help define the market.

Most financial institutions in India do not offer specialised products for EVs, except for the SBI Green Car Loan scheme. In Norway, China, the UK, Australia and other countries, most leading banks offer such products, contributing to high EV adoption rates. Financial institutions are also risk averse due to the lack of reliable data on EV performance – in terms of range, asset life, maintenance requirements, load capacity and more – especially in the Indian context.

There are also utilisation risks. For example, public charging infrastructure is still being built in most cities. For fleet operators, utilisation depends on drivers being able to use these charging stations. Charging at home is not always an option for drivers, given grid reliability and parking challenges. Such uncertainty and risk can lower the confidence of organised finance in financing fleets for this use case.

Government interventions

To lower the TCO of EVs, most government initiatives at present have provided capital expenditure (capex) and annual operating expenditure (opex) incentives. Prominent interventions aimed specifically at financing include the Department of Heavy Industry recommending an opex-based model by NITI Aayog to state transport undertakings. The model will deploy a total of 5,595 e-buses under FAME II. Further, the Delhi EV Policy provides an interest rate subvention of 5 per cent on loans for buying e-autos and e-carriers. The Delhi Finance Corporation and its empanelled scheduled banks and non-banking financial companies are developing a scheme on interest rate subvention. The policy aims at bringing more traction to this price-sensitive and financially challenging segment. Also, the Kerala Finance Corporation has created a programme to provide low-cost loans to EVs in the state. Buyers make a 20 per cent down payment and avail of a 3 per cent point interest rate subsidy, resulting in an interest rate of 7 per cent. Loans are capped at Rs 5 million and have tenors of up to five years

Next steps

Next steps

End-user financing for EVs can be mobilised through financial instruments that directly address challenges and reduce risks in the short term, medium term and long term.

The inclusion of EVs in the RBI’s priority sector lending guidelines would incentivise banks to increase lending towards the sector. Interest rate subvention could also substantially improve the affordability of loans. They have already been enacted in other sectors and at the state level for EVs in Delhi.

Reducing uncertainties associated with EV models will improve their bankability. OEMs can provide assurance in the form of guarantees (to financial institutions- and warranties (to buyers) on the performance of their products.

Mechanisms and facilities that partly or entirely cover possible losses associated with financing EVs (due to their unclear resale value) can be capitalised at the national or multilateral level. These would distribute risk and provide financial institutions with an opportunity to build their trust in the sector.

Fleet operators and final-mile delivery companies can leverage their existing financial relationships to provide partial credit guarantees and utilisation guarantees to driver partners. Industry-led buyback programmes and battery-repurposing schemes will help OEMs and the central government catalyse a secondary market for EVs. This would improve the residual value of EVs, providing financial institutions with an avenue for resale in the case of borrower default.

Ecosystem enablers could include digital sourcing, underwriting and sanctioning, which can streamline EV loans by helping overcome operational and logistical challenges of vehicle financing. Also, piloting and commercialising new business models, combined with the flow of patient capital, can demonstrate the potential of the sector. Convening stakeholders from the financial industry, OEMs, fleet operators, government, and others can help prioritise EV financing. Last but not the least, identifying actionable steps is key to working towards implementation. In addition, financial institutions need help to understand the EV technology and business models, and stay up to date with the policy landscape. Educational materials can help lower risk and increase confidence. Finally, innovative procurement and leasing initiatives that lead to early deployments at scale can help prove the techno-economic viability of EVs and increase supply chain investments.