Demand-side management (DSM) is a mechanism to influence a customer’s capability and willingness to reduce or modify electricity consumption. It promises a reduction in costs and financial savings for consumers, while helping utilities operate efficiently. DSM is one of the key components of smart grids, which enables efficient and reliable grid operation. The evolution of smart grids in India will enable consumers to make more informed decisions about their energy consumption, helping them adjust both the timing and quantity of their electricity use.

About DSM

In an electricity grid, power consumption and production must be balanced at all times; any significant imbalance could cause grid instability or severe voltage fluctuations, resulting in failures within the grid. Over time, capacity augmentation has not been able to keep pace with the demand, resulting in energy and peak shortages in India. Also, capacity augmentation implies a massive investment requirement, long gestation periods for power projects, insufficient fuel supply and higher imports, and well-integrated transmission and distribution (T&D) infrastructure to support supply augmentation and environmental concerns. DSM works the other way round – instead of adding more generation to the system, it pays energy users to reduce consumption. DSM capacity is typically cheaper and easier to procure than traditional power generation.

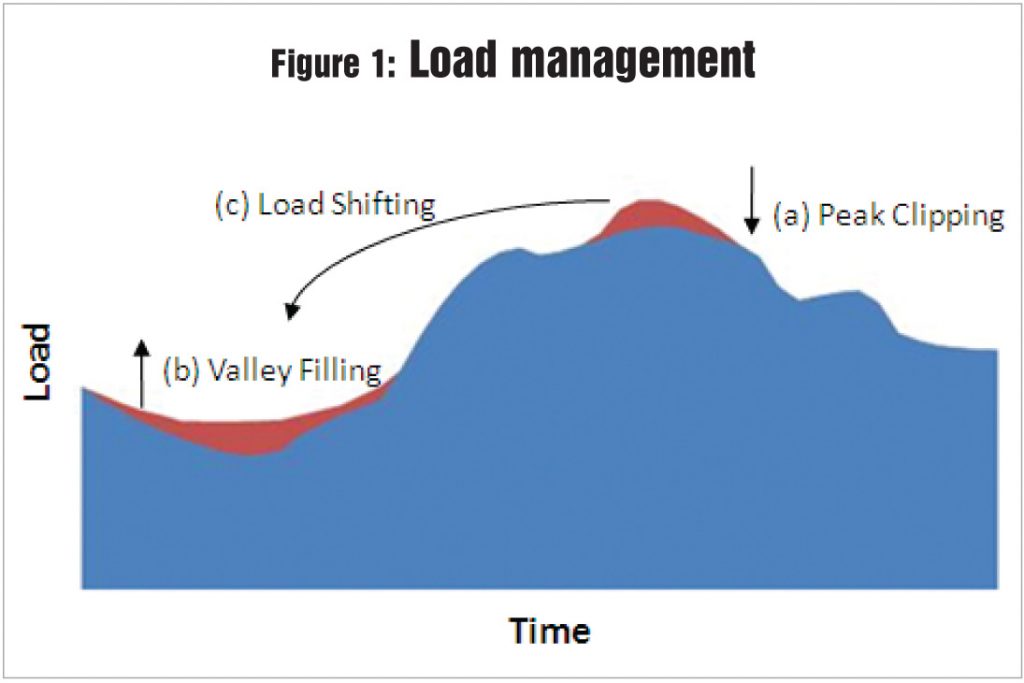

To achieve a high level of reliability and robustness in power systems, the grid is usually designed for peak demand rather than for average demand. This usually results in an underutilised system. In this respect, DSM programmes help in shaping the energy consumption pattern of users in order to reduce the peak-to-average ratio in load demand and to use the available generating capacity more efficiently.

DSM not only provides an alternative to new generation and T&D networks, but also reduces expensive peak power purchase, helps stabilise the grid, prevents outages, increases the load factor, improves system efficiency and reduces greenhouse gas emissions.

DSM comprises two main activities – energy efficiency and conservation, and load management. Energy efficiency and conservation programmes allow consumers to use less energy while receiving the same level of end-service, such as when they replace an old refrigerator with a more energy efficient one.

Load management, on the other hand, redistributes energy demand to spread it more evenly throughout the day. It allows energy users to act as “virtual power plants”, which help in stabilising the grid by voluntarily lowering or increasing the demand. Load management programmes can help reduce critical peak demand (Fig. 1 [a]), build loads for periods with very low demand (Fig. 1 [b]), and also transfer loads from periods of high demand to off-peak periods (Fig. 1 [c]). It can also take the form of strategic load growth and conservation.

DSM options include the use of energy efficient equipment such as lighting, air conditioning and refrigeration, renewable energy-based equipment like solar water heaters and pumps, apart from awareness programmes, load shifting including differential pricing and incentive-based programmes. In its wider definition, DSM would also include options such as renewable energy systems, combined heat and power (CHP) systems and storage systems. DSM can be viewed as an alternative cost-effective immediate “resource” option that offers to bridge the demand-supply gap.

DSM in India

Globally, the DSM programmes began in the US in the 1970s as a response to the growing concerns about the dependence on imported oil and the environmental consequences of electricity generation. In India, DSM started with the formation of an energy conservation cell within the Department of Power in the mid-1980s and the development of the Energy Management Centre in 1989. Further steps towards the promotion of DSM as a tool for balancing demand and supply have been the introduction of the Energy Conservation Act in 2001, the establishment of the Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE) in 2002 by merging the erstwhile Energy Management Centre, and through policies and legislations, including the Electricity Act, 2003 and the National Electricity Policy, 2005.

In the 1990s, a few DSM programmes were undertaken by utilities such as Ahmedabad Electric Company Limited (first utility-driven DSM programme), the Haryana State Electricity Board, the Orissa State Electricity Board and GRIDCO (the transmission utility of Odisha).

While initial attempts were focused more on energy conservation, DSM programmes began to be undertaken on a wider scale during the Tenth Plan (2002-07). It included lighting, agriculture pumping, awareness creation time-of-day (ToD) tariffs. Model DSM regulations were formulated in 2010 and DSM cells have been formed in many utilities. The Bachat Lamp Yojana (CFL promotion scheme) and the Domestic Efficient Lighting Programme (DELP) (LED promotion scheme) have been flagship DSM programmes in lighting.

In addition to lighting, various utilities have undertaken programmes for energy efficient air conditioners, refrigerators, ceiling fans, water pumps, etc. Some of the DSM programmes undertaken in India are the Lighting Initiative of the Bangalore Electricity Supply Company, the Agriculture DSM programme in Maharashtra, and the Municipal Water Pumping programme in Gujarat.

Till date, more than 90 per cent of utilities have already adopted ToD tariffs in their tariff structure, though mostly for a segment of industrial sector consumers. A more evolved form of DSM, that is ,demand response (DR), programmes, has not yet scaled up in India, but efforts on this front have begun. Only Tata Power and Reliance have undertaken pilot DR programmes, in Mumbai. Tata Power has also implemented a DR programme in Delhi, which is the first utility-initiated advanced metering infrastructure-based automated DR programme in India. A number of smart grid pilot projects are being implemented across the country with various functionalities, including peak load management and outage management. Most of these projects entail the development of a ToD/dynamic pricing mechanism as part of DSM.

Apart from utility-driven DSM measures, there have been efforts by energy service companies, the BEE, the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, the Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency and other government agencies to implement DSM. The BEE’s efforts can be seen in its programmes like Star Labelling and the Perform Achieve Trade (PAT) scheme.

However, there are various barriers in optimal implementation of DSM in India, including lack of information and awareness, access to financing, lack of sufficient financial incentives for the utilities as well as consumers, lack of expertise and infrastructure, and non-availability of protocols for monitoring and verification.

Smart grids and DSM

While a number of energy efficiency and conservation programmes have been implemented in India, load management and DR programmes have been confined mostly to ToD tariffs and a few pilots.

One of the main goals of DSM is to be able to charge the consumer the true price of energy at various points of time. If consumers could be charged less for using electricity during off-peak hours (low-cost periods), and more during peak hours (high-cost periods), then supply and demand would theoretically encourage the consumer to use less electricity during peak hours.

However, the variations in costs are usually not known to retail users and they are charged an average price only. To alleviate this problem, various time-differentiated pricing methods have been developed, which include day-ahead pricing, ToD pricing and critical-peak-load pricing; however, their implementation remains constrained by the lack of communication systems and smart meters at the consumer end.

Smart grids provide the required scale and scalability to make DSM cost effective and convenient through smart meters, which not only allow continuous metering and distance reading of energy consumption, but also enable consumers to connect to data on usage and prices of electricity and give utilities information about real-time demand and supply. By equipping users with two-way communication capabilities, smart grid systems make it possible to reflect the fluctuations of wholesale prices to retail prices and also allow utilities to collect data on usage and verify reduced demand. Smart grids also help in integrating information for a particular utility, thereby giving them a comprehensive view of all consumers. This enables utilities to develop targeted programmes for different consumer segments.

Apart from information on real-time pricing, smart grids enable a reduction in load by consumers on request in a DR programme. In some cases, they also provide remote control over consumers’ demand to the utility. Though not so relevant in the Indian context, smart grids also provide for charging systems for electric vehicles. These could also potentially be used to handle constraints in the grid during peak hours by using them for energy storage and for providing energy in the household when the car is not being used.

These technologies give the DSM those programmes being designed now and that will be designed by the utilities in the future a number of crucial advantages over those that were there in the past.

Conclusion

In spite of several efforts to promote DSM in India, with supporting policies also being there for quite some time, there has been little application of DSM in light of the enormous untapped potential that exists. While a number of small projects have been undertaken, Indian utilities have not been able to take DSM measures on a large scale yet. Though new technologies and smart grids are being implemented, they remain at a nascent stage and hence, there still remains a long way for DSM to be implemented to its full potential. Meanwhile, customer acceptance, which is a crucial factor in the successful implementation of DSM, should be enhanced through education and information and various market-based models should be tried out.