One of the long-standing wishes of the power industry has been to make the distribution segment self-sustainable by streamlining subsidies and introducing a direct benefit transfer (DBT) mechanism. Rightly so, the total subsidy dependence of the state-owned discoms for 2017-18 is pegged at a staggering Rs 810 billion, as per rating agency ICRA’s estimates.

Delays and non-payment of subsidies by the state governments are attributed to be one of the biggest contributors to the financial troubles of the distribution segment. These subsidies are meant to be paid to the discoms to compensate for cheaper power supplies to certain segments (primarily agricultural and domestic consumers). As per Section 65 of the Electricity Act, 2003, state governments should make the subsidy payment in advance to the state utilities for the following financial year. However, more often than not, the governments actually make the payments later.

So how does DBT help resolve the issue? “From the discoms’ perspective, it would help in the timely collection of cash and in improving the liquidity of discoms. From the overall power sector perspective, DBT would be positive as it entails payment of the full price of electricity by the consumer with subsequent reimbursement of subsidy,” explains Rakesh Mokashi, managing director and chief executive officer (CEO), CARE Ratings.

The DBT scheme is currently used for the cooking gas segment, in which the government pays subsidies directly into households’ bank accounts based on the cylinders purchased at full price from dealers. With this, the government did away with the previous system of compensating LPG distributors for selling to households at below-market prices, resulting in billions in savings on gas subsidies every year.

“The power distribution segment needs a DBT mechanism based on the same principle as the subsidy for cooking gas cylinders. If electricity is a social good, it has to be handled in the same way as cooking gas cylinders, so that the commercial viability of power distribution companies/entities is not adversely affected by this welfare measure,” says sector veteran and former power secretary Anil Razdan.

Urging the government to introduce DBT for power, Amitabh Kant, CEO, NITI Aayog stated at an industry event last year, “If this country has had the courage, determination to do the mammoth, unprecedented task of demonetisation and a huge, huge revolutionary move forward, then the country must have the courage and responsibility to introduce DBT for electricity. No consumer should get electricity without DBT.”

The government appears to be serious about the proposal to introduce DBT. In end-2016, an expert panel comprising senior officials from the states and the industry was constituted to study the proposal for direct subsidies for the power sector. Also, in a recent statement to the Financial Express, power secretary A.K. Bhalla stated, “The government is meticulously looking at several means to put the DBT scheme into action so that the benefits reach only the intended beneficiaries.”

Can DBT be successful for the power sector? What are the preparatory steps needed for this mechanism to work? What are the key implementation concerns? Power Line presents its perspective on these issues…

Case for DBT

While the Ujwal Discom Assurance Yojana (UDAY) is attempting to address the legacy issue of subsidy dependence and bring tariffs in line with costs, many sector experts feel that a long-term sustainable solution calls for the introduction of measures such as DBT, otherwise there may be a need for another round of debt restructuring.

“UDAY has helped in correcting the unviability of discoms by reducing the burden of interest on loans. DBT will push the economics of the power industry further along in the right direction,” says Raghumatta Rao, chief mentor, ICRA Group, and formerly managing director and CEO, ICRA Management Consulting Services Limited.

The country’s apex planning agency, NITI Aayog, in the recently released National Energy Policy has also noted that the power sector must implement the DBT mechanism for subsidy disbursal. “The adoption of DBT will meet the twin goals of curbing wasteful consumption and also deliver subsidy to the meritorious efficiently. Distribution companies should pay full market-determined price to generation companies and receive the same from customers with the latter compensated through DBT,” notes the report.

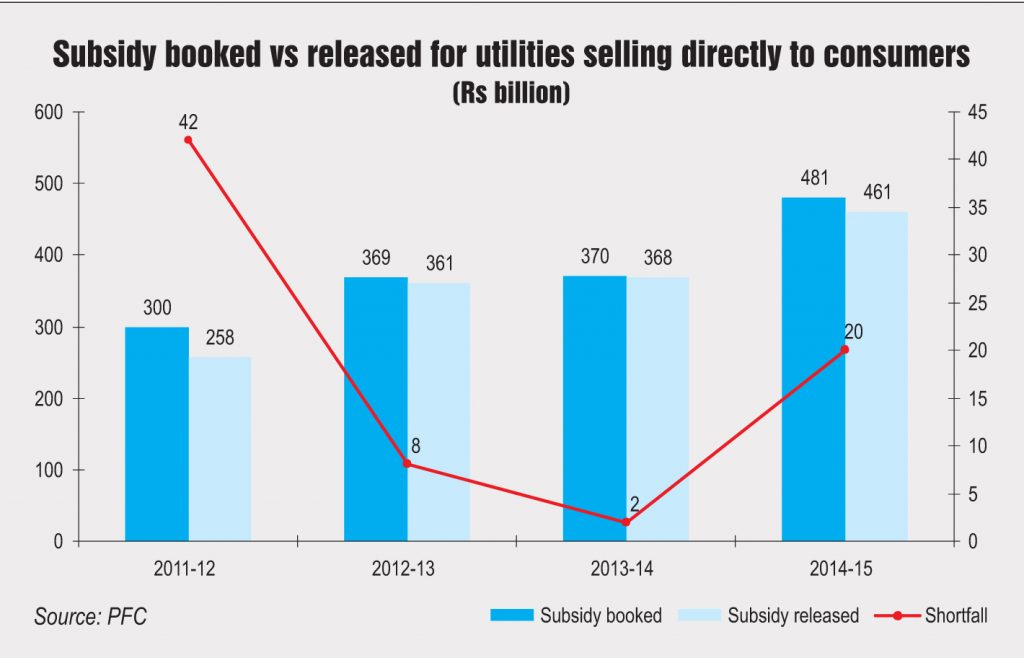

According to Power Finance Corporation (PFC) estimates, of the Rs 481.81 billion subsidy booked in 2014-15, the subsidy released was only Rs 461.12 billion. (The actual subsidy payment to the utilities is termed as “subsidy released” and the lump sum amount that the state governments announce to be disbursed to utilities as compensation is “subsidy booked”.) The subsidy released by the state governments has been lower than the requirement over the past few years. The subsidy received as a percentage of the subsidy booked was 97.8 per cent in 2012-13, 99.21 per cent in 2013-14 and 95.71 per cent in 2014-15.

In 2014-15, as per PFC, the subsidy requirement was pegged at around 13 per cent of revenues. While PFC’s estimates for further periods are not available, according to ICRA, the subsidy requirement is estimated at 17-18 per cent of the revenue requirement approved or estimated for the utilities for 2017-18.

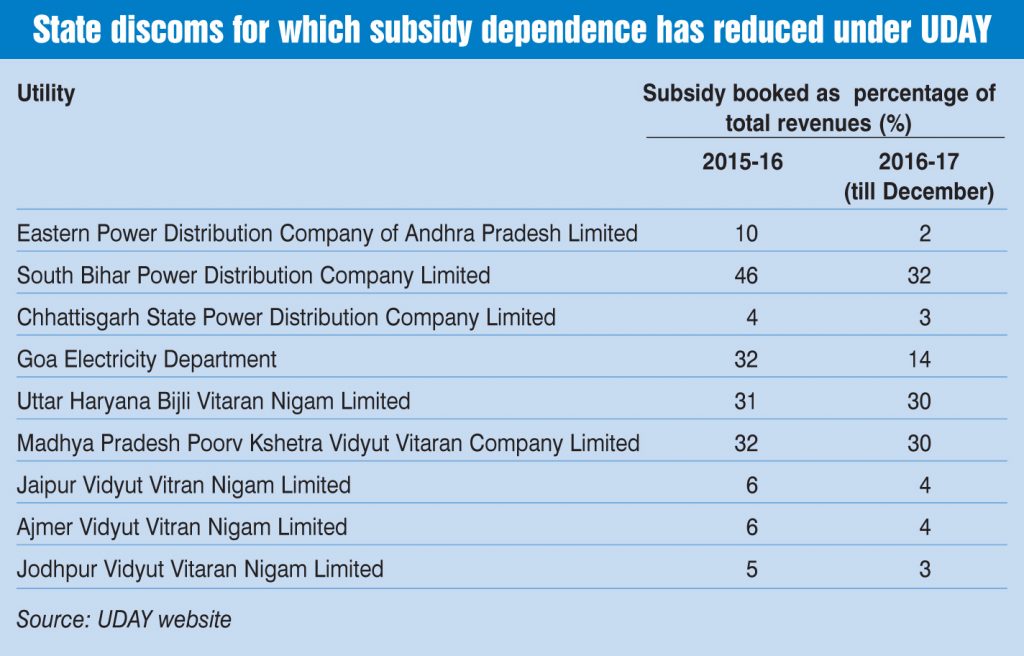

Further, ICRA notes that the dependence on subsidy support for discoms in states such as Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Gujarat, Karnataka, Haryana, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu and Telangana continues to be significant, ranging from 11 per cent to 29 per cent of the overall revenue requirement across the states.

Moreover, the pricing system at present is unviable with the average cost of power being higher than the average revenue realised.

“There are certain consumer segments that are affluent but pay tariffs lower than the average cost of supply. A DBT scheme, particularly for household and agricultural segment consumers, will correct such wasteful support and enable subsidies to be directed to the genuinely needy people,” adds Rao.

How does DBT work?

While the original DBT scheme for LPG subsidies, named Pratyaksh Hanstantrit Labh (PAHAL), was launched in June 2013, the NDA government modified and relaunched the scheme in 54 districts in November 2014 and in the rest of the country in January 2015. The idea was that consumers link their Aadhaar number to a bank account and receive the subsidy amount for 12 cylinders in a year. Those without an Aadhaar number could furnish any other bank account to receive the subsidy.

While this ensured that all LPG consumers could, in theory, avail of the subsidy, it also meant that a large proportion of the subsidies were going to people who could afford LPG cylinders at the unsubsidised rate. Towards this, from December 2015 onwards, it was subsequently decided that people earning more than Rs 1 million a year would not be eligible for the LPG subsidy. According to the government’s estimates, savings due to DBT in LPG had touched nearly Rs 264.08 billion till February 2017.

For DBT to work for power consumers, either bank transfers could be considered or appropriate deductions made from electricity bills. “Eligible electricity consumers should preferably get the DBT in a parallel transfer transaction on full payment of their electricity bill, or else the fixed monthly DBT amount could be deducted from the monthly bill raised by the discom, and the discom compensated simultaneously by the concerned state government,” says Razdan.

He, however, cautions that as electricity is a concurrent list subject, unlike petroleum and natural gas, which are central subjects, each state government would need to fix its own level of DBT/subsidy depending on affordability and policy priority. That said, DBT for power is likely to be more efficient than DBT for cooking gas cylinders, which involves a labour-intensive gas cylinder filling, transportation and supply programme, he adds.

Implementation challenges

The unanimous view is that DBT for the power sector is a more challenging proposition than that for LPG and requires significant political and regulatory support. One of the biggest challenges, according to experts, would be reliable metering. Several consumer categories such as agriculture and slum tenements are not metered at the individual level. Further, smart metering would be necessary in the case of time-of-day electricity tariffs and rooftop solar. An associated challenge would be ramping up the billing and collection infrastructure, which would entail further investments for the already cash-starved discoms. Another key challenge would relate to overcoming resistance from customers as they would now have to pay the entire bill upfront.

“Unlike LPG cylinders, where the subsidy amount is identified and the involvement of the monthly subsidy amount is lesser, the success of DBT of subsidy in the power sector would be an uphill task for the government,” notes Mokashi.

This could result in protests from misinformed consumers. Also, the financial position of discoms could deteriorate further, as they may need to fork out higher direct transfers for subsidised consumers to overcome the tariff shock.

Also, unlike oil marketing companies, which have years of mature marketing orientation, discoms have been largely operating as monopolies. Hence, sensitisation of discoms to consumers and building insitutional capacity of discoms to train them for customer interface and satisfaction would be important steps before implementing such a regime.

Most importantly, the move to DBT would require a change in the regulatory approach for tariff fixation. “The regulatory process for tariff fixation should migrate from a regime of cross-subsidisation to one that is based on full cost recovery for every consumer based on economic principles,” notes Rao. Another major challenge relates to the banking network, which is the backbone of the DBT system. Banking penetration among the target beneficiaries is still quite limited, especially in rural areas. The database of consumers will need to be validated to ensure there are no duplications or missing consumers.

The way forward

The best possible time for introducing the DBT scheme according to power experts is along with UDAY. “It should have been done yesterday,” comments Razdan. He adds that this is much needed to clear the blurred lines between the desired commercial nature of discom operations and the welfare objectives of state policy.

The mechanism would need some fine-tuning and commensurate development of appropriate regulatory processes, installation of meters, appropriate identification and banking systems for it to work effectively. “While a nationwide roll-out may be difficult in the short term, a few pilots would need to be tried first,” says Rao.

Net, net, DBT is an idea whose time has come as it will help achieve a healthy fiscal situation as well as reinforce the growth momentum provided by other structural reforms ongoing in the sector.

Reya Ramdev (The views expressed by Raghumatta Rao in this article are his personal views.)

Be the first to comment