Reducing emissions from coal-based power plants has been one of the key focus areas of the government. In December 2015, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) came out with standards for sulphur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen oxide (NOx), mercury and suspended particulate matter (SPM) emissions by thermal power plants (TPPs). Prior to this, there were no rules to control SO2 and NOx emissions at TPPs in India, which account for a significant share of the annual emissions from these two pollutants.

These standards were proposed to be implemented by all the existing units by December 2017, whereas the plants commissioned after December 31, 2016 were required to meet the standards right from commissioning. However, even after more than three years of the notification of standards, the compliance of TPPs is really low. This can be attributed to the limited experience of TPPs with emission control technologies, long shutdown periods, space constraints in the installation of various emission control technologies, and lack of clarity on the pass-through of additional costs incurred in complying with these norms. While efforts to resolve these issues have shown some progress, most of the state and private developers are still undertaking feasibility studies to identify the best-suited technology.

Reducing SO2

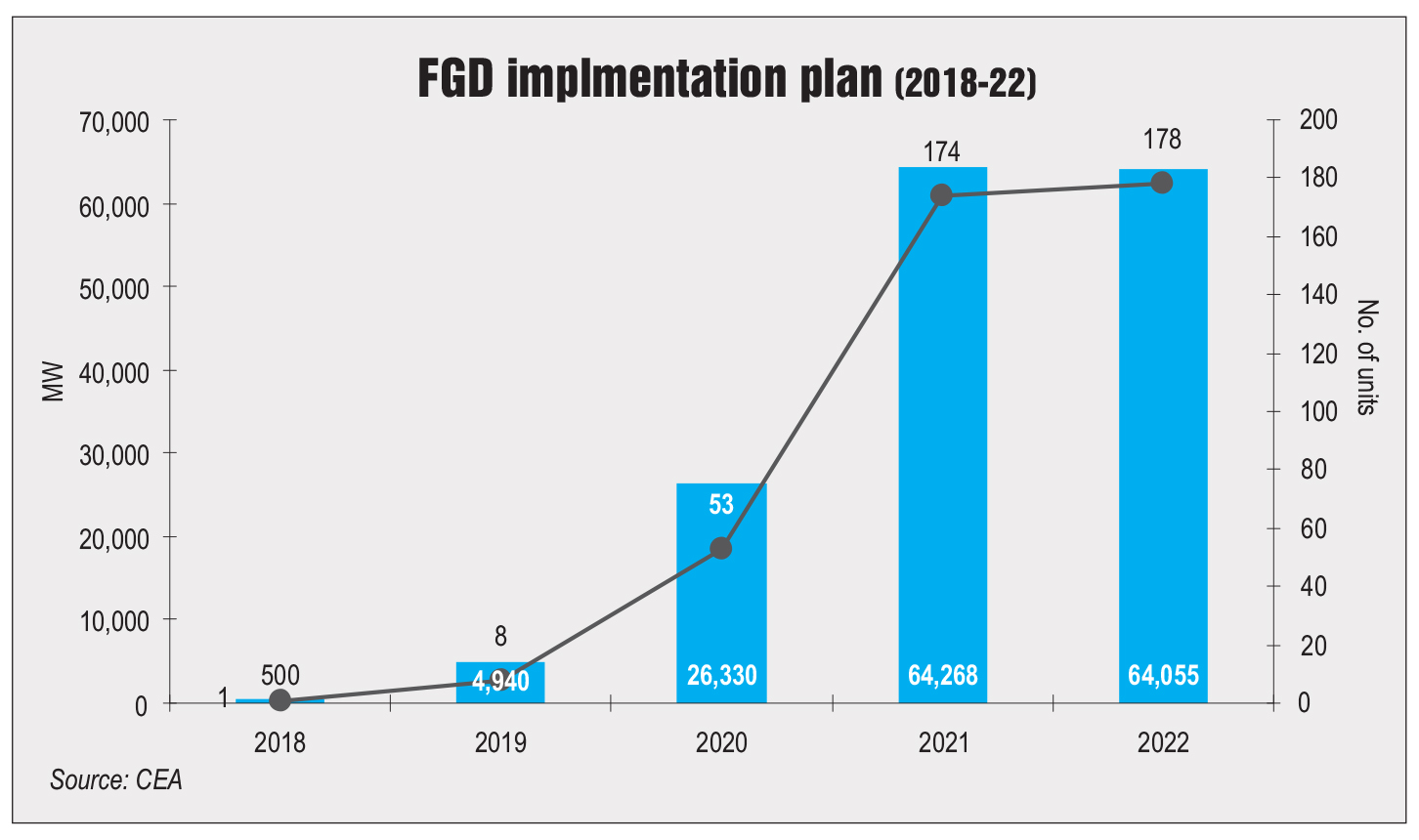

For SO2 control, flue gas desulphurisation (FGD) has been identified as one of the key technologies to comply with the emission standards. The Central Electricity Authority (CEA), along with regional power committees and generation companies, has prepared a phased FGD implementation plan. Since all the plants cannot be shut down simultaneously (because it requires 30-36 months for the entire process), the implementation has been planned in such a way that sufficient capacity is operational at all times.

As per the implementation plan, of the 414 units (160.1 GW), around 350 (128.3 GW) will complete the installation of FGD systems by 2021 and 2022. NTPC, the largest public sector player in thermal power, is in the lead. The company has a capacity of about 64 GW with FGD systems (43 GW excluding joint ventures) at various stages of implementation. Among the state gencos, Maharashtra State Power Generation Company has the highest planned capacity for FGD at 9.6 GW, followed by Uttar Pradesh Rajya Vidyut Utpadan Nigam Limited at 5 GW and Karnataka Power Corporation Limited at 5 GW. The private players with maximum planned FGD installations include Adani Power (8.4 GW), Tata Power (5.7 GW) and Reliance Power (3.9 GW).

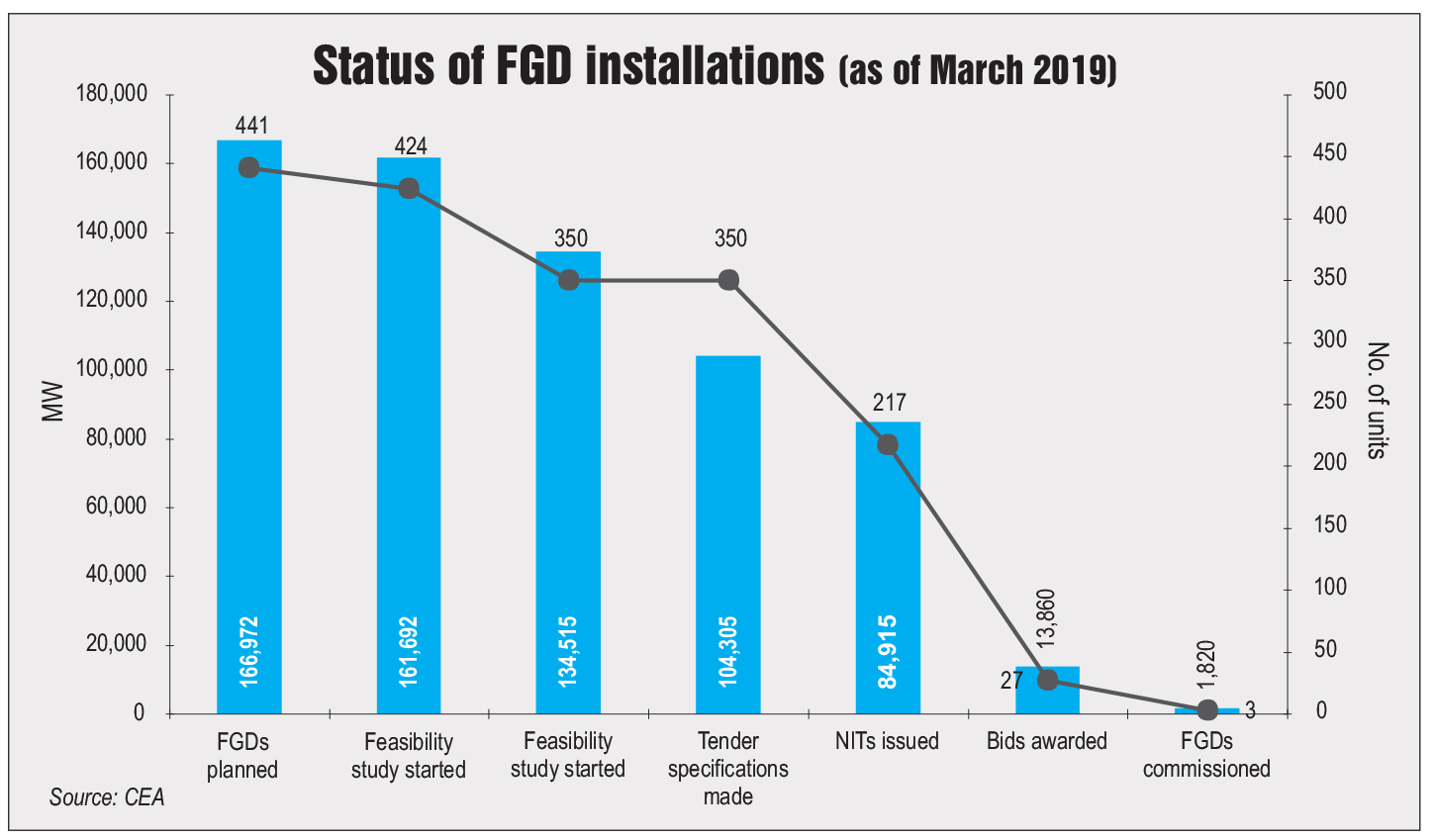

While the plan was made for 414 units with an aggregate capacity of around 160 GW (based on the existing coal-based capacity at the time), the total capacity for which FGDs are planned currently stands at 166.9 GW (across 441 units) after taking into account the units commissioned between August 2017 and March 2019.

As of March 2019, FGD systems were commissioned at only three units aggregating 1,820 MW, as per the CEA. These are two 660 MW units of CLP India’s Mahatma Gandhi Thermal Power Station (TPS) and one 500 MW unit of Tata Power’s Trombay TPS. Apart from these, NTPC commissioned its first FGD at the 500 MW Vindhyachal TPP in 2018. Bids have been awarded for 27 other thermal power units aggregating 13,860 MW. Further, tender specifications have been finalised for over 100 GW of capacity, of which tenders have been issued for nearly 85 GW while the remaining capacity will be up for bidding soon. Meanwhile, about 90 units with a capacity of over 30 GW are yet to complete the feasibility studies. About 6.5 GW of capacity claims to be SO2 compliant, however, the Ministry of Power has written to the MoEFCC and the Central Pollution Control Board to check the SO2 emission levels of this capacity.

As of March 2019, FGD systems were commissioned at only three units aggregating 1,820 MW, as per the CEA. These are two 660 MW units of CLP India’s Mahatma Gandhi Thermal Power Station (TPS) and one 500 MW unit of Tata Power’s Trombay TPS. Apart from these, NTPC commissioned its first FGD at the 500 MW Vindhyachal TPP in 2018. Bids have been awarded for 27 other thermal power units aggregating 13,860 MW. Further, tender specifications have been finalised for over 100 GW of capacity, of which tenders have been issued for nearly 85 GW while the remaining capacity will be up for bidding soon. Meanwhile, about 90 units with a capacity of over 30 GW are yet to complete the feasibility studies. About 6.5 GW of capacity claims to be SO2 compliant, however, the Ministry of Power has written to the MoEFCC and the Central Pollution Control Board to check the SO2 emission levels of this capacity.

With respect to the progress of various gencos, NTPC has awarded contracts for 31.81 GW, nearly half of its planned capacity, while another 28.05 GW of capacity is at various stages of tendering. Apart from NTPC, only Tamil Nadu Generation and Distribution Corporation Limited (630 MW) and Punjab State Power Corporation Limited (920 MW) have awarded projects so far. Gencos including the Damodar Valley Corporation (DVC), Uttar Pradesh Rajya Vidyut Utpadan Nigam Limited (UPRVUNL), Karnataka Power Corporation Limited and Jindal Power have issued tenders for more than 60 per cent of their respective planned FGD capacities. Jindal Power has issued tenders for all of its 3,400 MW capacity planned for FGD implementation. Meanwhile, Adani Power and Reliance Power have prepared the tender specifications for the entire planned capacity and are expected to issue the tenders soon.

NOx control

NOx control

For curtailing NOx emissions, various technologies are available that can help in the reduction of NOx levels. These include selective catalytic reduction (SCR) and selective non-catalytic reduction (SNCR) systems, and over fire air (OFA) and low NOx burners (LNBs). OFA and LNB are already being used in India, but they are capable of reducing the NOx emissions only up to 600 mg per Nm3. The NOx limit for newer plants is 100-300 mg per Nm3, for which post-combustion denitrification systems such as SCR and SNCR are required. However, they have not yet been proven suitable for Indian coal, which has high ash content. SCR systems also require ammonia as a de-nitrification agent (about 2,500 tonnes per year for a 500 MW unit). The arrangement for availability, transportation, handling and storage for such large quantities of ammonia is yet to be addressed by gencos. Various pilot studies are being undertaken to understand the performance of SCR and SNCR systems in the Indian context. For instance, NTPC is undertaking eight projects for SCR and two for SNCR. These pilot projects are likely to be completed by May 2019. The SCR pilots are being conducted at the Vindhyachal, Rihand, Korba, Simhadri (two projects), Ramagundam, Sipat and Kahalgaon TPPs and SNCR tests are being conducted at the Rihand and Vindhyachal TPPs. The findings of these pilot projects will play a significant role in determining a suitable technology solution for reducing NOx emissions.

Challenges and outlook

Challenges and outlook

Progress on the implementation of emission control systems has been slow owing to a mix of reasons. One of the key factors is the additional capex and opex requirements for the implementation of FGD and other emission control systems. While this issue has been addressed to a certain extent, with the cost being allowed as a pass-through in tariff, plant owners have been facing difficulties in arranging funds. Banks and other financial institutions have been reluctant to fund these investments due to the high level of stress in the sector. In October 2018, the minister of state (independent charge) for power and new and renewable energy held a meeting with bankers regarding lending for the installation of pollution control equipment.

Further, very few power producers in the country have prior experience in the selection, procurement, commissioning, and operations and maintenance of air quality control systems. To this end, in December 2017, the CEA issued standard technical specifications for retrofitting of wet limestone-based FGD systems in typical 2×500 MW coal-based power plants. The CEA also issued an amendment to the above specifications in October 2018. It mainly deals with the issue of chimney height in view of the MoEFCC notification dated June 28, 2018. Meanwhile, a suitable technology solution for NOx reduction is yet to be identified for high ash Indian coal. NOx emission norms in India are very stringent vis-à-vis other countries.

For FGD systems, the unavailability of good quality limestone, one of the key raw materials, poses a major challenge. The CEA is in discussions with the Ministry of Mines regarding the limestone requirement at power plants. Further, when all plants have operational FGD systems, around 38 million tonnes of gypsum would be generated every year. The disposal/utilisation of such a large quantity of gypsum is a cause for concern. The MoEFCC has formed a group to suggest ways for the disposal of gypsum and calcium sulphite. Also, SCR systems require ammonia as a denitrification agent (consumption of about 2,500 tonnes per year for a 500 MW unit). The availability of large quantities of ammonia as well as facilities for its transportation, handling and storage needs to be ensured before installing SCR systems.

At the current pace of execution, meeting the timelines seems difficult. The gencos need to fast-track the installation of pollution control equipment. The utilities will also take guidance from the CEA with respect to technologies and the costs involved on a case-to-case basis. The feasibility of a technology depends on various factors including unit capacity, vintage and location; operational performance parameters and opex requirement; and gross calorific value of coal and its sulphur content. So far, the CEA has received only six such proposals. Meanwhile, the government needs to track the progress in project implementation more closely.