The Security Constrained Economic Despatch (SCED), which facilitates the supply of cheaper electricity based on merit order, has been under implementation since April 1, 2019. It is part of a six-month pilot for thermal interstate generating stations (ISGSs). Power System Operation Corporation of India (POSOCO), the implementing agency of SCED, submitted its interim report on the subject to the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC) in August 2019. According to the report, during the first four months, the optimisation of 49 thermal ISGSs under SCED with an installed capacity of about 56 GW has contributed to a reduction in generation costs up to Rs 33 million. Further, it has been observed that the available spinning reserves in the higher variable cost generators have been consolidated. So far, POSOCO has published 17 weekly settlement statements up to the week of July 28, 2019.

Recently, in a suo motu order released on September 11, 2019, the CERC acknowledged the experience gained in optimisation at the ISGS level and extended the period of the pilot project by another six months up to March 31, 2020. The regulator has also developed a method for sharing the surplus on account of the reduction in generation costs. The extension will help the system operator gain further experience in the winter season as well.

“SCED has enabled the achievement of pan-India, multi-area optimisation without disturbing the freedom or choice of any utility,” says S.K. Soonee, adviser, POSOCO. Power Line presents the key developments in SCED implementation…

Background and SCED implementation

On January 31, 2019, the CERC issued a suo motu order directing POSOCO to implement the SCED optimisation model for all ISGSs that are regional entities and whose tariff is determined or adopted by the CERC for full capacity. This was to be done on a trial basis for six months from April 1, 2019, honouring grid security and the existing scheduling practices prescribed in the Indian Electricity Grid Code (IEGC). The order was issued in response to a consultation paper, “SCED of ISGSs Pan India”, published by POSOCO in September 2018.

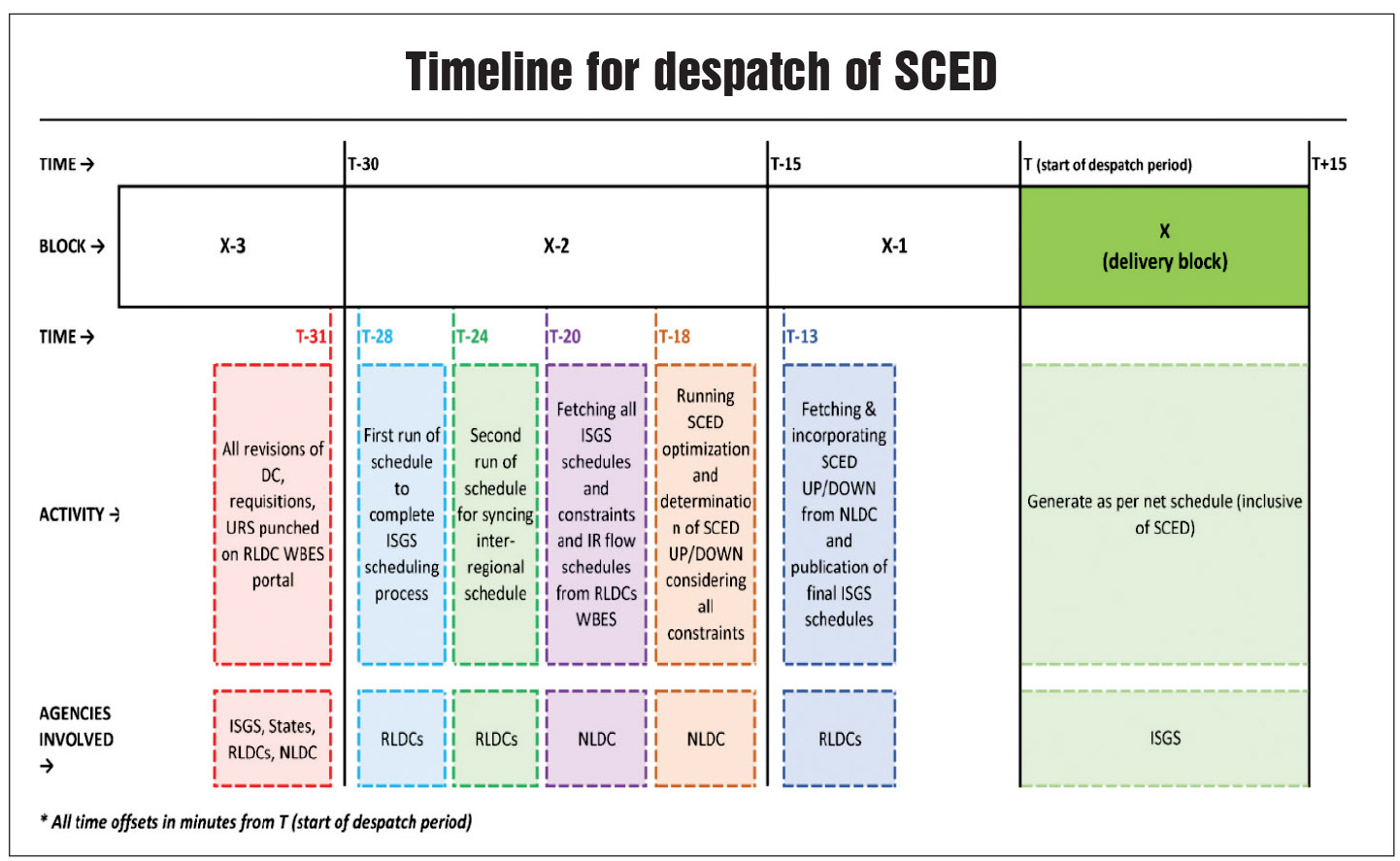

The SCED process has effectively created a thin, centralised layer of optimisation over the existing decentralised scheduling system. The freedom of state utilities to revise their requisitions up to the fourth time block ahead of the delivery block (or effectively up to 30 minutes before delivery) has been retained while executing the SCED pilot. To begin with, multifuel-based stations have been excluded as they use multiple types of

fuel, resulting in complexity. The implementation of SCED within two months was a challenging task for POSOCO as it involved a host of activities including software development, interface creation, improvement in the intercontrol centre communications systems, information dissemination in real time and streamlining of the settlement system.

The pilot gave the National Load Despa-tch Centre (NLDC) a direct role in the scheduling process. A scheduling server has been made available at the NLDC for the collation of schedules and fast data exchange with the RLDCs. POSOCO has developed the software outline and data flows through in-house efforts. The optimisation core engine uses the general

algebraic modelling system software, which is a high-level modelling and solver system for optimisation. Multiple inputs go into the SCED algorithm every 15 minutes, namely, DC, normative on bar capacity, injection schedules, ramp-up and ramp-down rates, variable charges as declared in reserves regulation ancillary services (RRAS), technical minimum as per the IEGC provisions, and interregional schedules and transfer margins (see figure).

The optimal schedule for SCED generators is relayed to the RLDCs for incorporation into the ISGS schedules about 15 minutes before the despatch interval begins. The mathematical formulation includes the objective function of minimising the pan-India ISGS variable cost. It is subject to constraints of the need to meet the total requisition of states by ISGSs, available transmission capability, technical minimum of plants, maximum generation and ramp-up/down rates.

The optimisation algorithm was improved after almost three weeks of pilot operation and made more robust to deal with infeasibility and ride-through within the given constraints (of system ramp rate, interregional schedule exceeding transfer capability limits, finite reserves and individual generator ramp rate) in real time. This is done by adding artificial variables to constraints and penalising the objective function.

CERC suo motu order

Besides extension of the pilot, the CERC order specifies the method of sharing the net savings accrued in the National Pool Account (SCED) among stakeholders. The pool is maintained by the NLDC. Previously, the CERC had accepted the sharing of benefits in principle but the sharing methodology was to be decided after taking into account the pilot results and the extent of savings available. In line with this, the regulator, in its order, has directed POSOCO to modify the SCED procedure to incorporate the sharing method. The net benefits accrued in the pool after adjusting the compensation for part load operation of generators are to be shared in the ratio of 50:50 between generators and discoms on a monthly basis. Among discoms, the 50 per cent share would be based on their final schedule from stations covered under the SCED pilot as per their Regional Energy Account (REA). Among generators, the benefits will be shared between SCED-up and SCED-down generators in the ratio of 60:40 for each time block. This is based on the ratio of number of generators that received SCED-up and SCED-down signals during the pilot. While preparing the REAs, the regional power committees (RPCs) must provide and settle monthly benefits for each SCED generator.

It may be noted that POSOCO, in its interim report, had proposed that the residual savings in the National Pool Account (SCED) may be shared among the state utilities, generation ISGSs and the interstate transmission system. It could also be used for innovation and research. For now, the regulator has restricted the sharing of savings only between the first two entities.

Key findings of POSOCO’s interim report

During the four-month pilot period, 49 coal- and lignite-based ISGSs with 132 generating units and an installed capacity of 55,940 MW participated in SCED. The daily average perturbation (by decreasing costly generation and increasing cheaper generation) was 1,276 MW, while the average system marginal price (SMP) was Rs 2.98 per unit. A reduction of Rs 3.3 billion in system cost was achieved during the period after deducting Rs 582.8 million towards heat rate compensation for southern region generators (see table).

The post-SCED cost (total variable cost of generation after SCED) was about Rs 30 million less on a daily basis than the cost before SCED (variable generation cost of plants’ scheduled requisition).

Key benefits

The following are some of the key benefits of SCED:

- Optimisation of generation based on merit order: Generation from pithead plants with lower variable cost in the northern and eastern regions was increased while generation with higher variable costs was decreased in the southern region. Generation optimisation has been achieved across the country with the reduction of production costs.

- Reduction in fuel costs: About 1.5 per cent reduction in generation costs has been achieved translating into a reduction of 3.3 paise per kWh in the average variable cost of generation.

- Ease of operation: A 43 per cent reduction in the number of schedule changes has been achieved along with a 34 per cent reduction in schedule (in megawatt) changes. This has increased the plant load factor of cheaper stations and decreased it for costly stations.

- Diversity: During holidays or weekends, there is a higher reduction in fuel costs. Further, during extreme weather conditions, load crash results in the schedule being revised to a technical minimum within the region.

- Wider ambit: In June 2019, NTPC’s 800 MW Gadarwara power station in Madhya Pradesh and Tata Power’s 1,050 MW Maithon power station in Jharkhand were incorporated in the SCED optimisation process. The robustness of the application was demonstrated by the successful incorporation of generators in the software application and interfacing the generators without any disruption to the ongoing SCED process (every 15-minute time block).

- Reduced congestion: The split in regional system marginal prices represents periods of transmission congestion.

Implementation challenges

The key implementation challenges pertain to:

- Information technology and data interfacing: Given the different web-based energy scheduling systems (WBES) across RLDCs, data interfacing is a key challenge. This requires a robust and seamless communication system.

- Communication and integration of regional scheduling software applications: Significant effort went into the integration of WBES across regions with automatic schedule preparation in each time block. The hardware and software across all RLDCs and at the NLDC had to be upgraded with tight data exchange and processing timelines.

- Self-healing/Ride-through attributes: An improved optimisation algorithm was formulated and deployed to make the application robust enough to run continuously in a real-time environment with self-healing/ride-through attributes to deal with infeasibility.

- Operational flexibility provisions in SCED: To tackle certain contingencies in the system, operational flexibility provisions were incorporated in the SCED application to facilitate operational requirements of the generators as well as regulatory compliances.

- Effect of SCED on ramping reserves: The availability of reserves is constrained by the ramping capability of generation units that have reserves, resulting in a reduction in the cumulative reserve quantum after the SCED optimisation process.

- Interregional scheduling: For effectively implementing the optimisation process across regions, it is necessary to change the scheduling methodology from corridor-wise scheduling to net-injection/net-drawal for each region. This would require amendments to the IEGC.

- Need for gate closure: Currently, schedules can be revised by giving a notice of four time blocks, resulting in multiple revision requests from participants on a continuous basis. It also poses problems in real-time assessment of the hot and cold reserves available in the system. The concept of gate closure is essential to bring more certainty in despatch, particularly in terms of the requirement and activation of reserves.

Review and stakeholder consultation

The concept of SCED was put up for stakeholder consultation and review at various points of time during the year. Interactions were held with RPCs and SCED generators prior to the commencement of implementation. Workshops were conducted, and academia and think tanks were consulted on various operational and implementation aspects. After the pilot was operationalised, interactions at the RPC level were conducted by the policymakers and regulators.

The way forward

Going forward, there is a need for expanding the ambit of SCED to all regional entity generators whose scheduling is done by the RLDCs. There are challenges with respect to stations which have entered into different types of contracts with multiple rates for different times of the day. For SCED, there is need for a single variable charge for each station as well as upfront declaration of technical parameters such as DC, technical minimum, ramp-up/down rates for each station. Therefore, a single variable charge needs to be computed based on a CERC-approved single rate or weighted average price of the contracts or any other mechanism. Further, the RPCs will find it difficult to calculate heat rate compensation for IPPs (competitively bid) in the absence of related regulations.

Concurrently, the process of optimisation of the intra-state generators must also commence. In this regard, a committee under the FOR technical committee has been formed for implementation in three states – Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Gujarat – to begin with. This will help in transferring the insights gained at the interstate level to the intra-state level as well.

The despatch of reserves could be improved by co-optimisation of SCED and RRAS despatch, which will bring greater certainty and efficiency in the delivery of the demanded reserve by the system operator in a cost-effective manner. However, to fit co-optimisation in the existing regulatory framework, a methodology has to be evolved. Simultaneously, POSOCO is in the process of preparing a detailed report on the implementation of SCED, as required in the CERC order (January 2019). It has also sought time to understand the complexities involved in the co-optimisation of energy and ancillary services, and test them on a pilot basis before the regulatory framework is finalised.

The SCED pilot has helped gain experience in optimisation at the ISGS level. It is a noteworthy initiative by POSOCO given the efforts taken to develop the software application in-house and address the various complexities in scheduling changes, data synchronisation, and communication. The plans to expand its ambit and gain further experience is a step towards pan-India optimisation of the power procurement cost.

Swarna Kesavan