By Prateek Aggarwal, Senior Analyst, and Vikas Chandra Agarwal, Director (Distribution), Uttar Pradesh Electricity Regulatory Commission

By Prateek Aggarwal, Senior Analyst, and Vikas Chandra Agarwal, Director (Distribution), Uttar Pradesh Electricity Regulatory Commission

India, home to one-sixth of the world’s population, is the fastest growing and the third largest economy in the world. Also the third largest producer of electricity, India added approximately 220,000 MW of power in the past two decades. However, it is unable to provide round-the-clock cheap power to industries, thereby impacting industrial growth, the GDP and the supply of 24×7 electricity to all.

It is a well-known fact that energy plays the most critical role in the economic growth of a country, specifically in industrial production. In order to overcome the power-deficit scenario in India, power sector reforms were commenced in 1991-92, with private players/developers being allowed to participate in capacity addition (today they contribute close to 42 per cent). However, the reforms process was not successful due to accumulated issues related to governance, inconsistent pricing and subsidy policies. With concerns mounting, the government introduced the idea of open access in the Electricity Act, 2003, a new concept that differentiated it from the Electricity Supply Act, 1948. Private players are contributing in a significant manner to open access, adding to the development of the power market and promoting competition therein.

Today, open access allows a buyer with a connected load of 1 MW or more to procure power directly from the market through the grid. It provides that the buyer has the option of selecting the seller and vice versa. The charges for utilising the transmission and distribution networks, and the quantum of power transmitted over it are easily discernible for effecting payments. As per the Electricity Act, open access to the distribution network owned by discoms was to be implemented in phases. Currently, some of the states are permitting open access to generators if they are connected to the central transmission network. However, in the case of buyers, only some states have permitted limited open access.

Open access, a cornerstone of power sector reforms and one of the key ingredients of the Electricity Act, has remained a largely unfulfilled aspiration across the country, even though the industry is reeling under the burden of high electricity tariffs. Discoms are the real hurdles in the implementation of open access and are unwilling to let their most lucrative customers bypass them and buy power from other sources, thus compelling industries to pay more despite the availability of cheaper power.

The reality, however, is more complex. In the present scenario, the irony is that open access has not been allowed to succeed for various reasons such as the apprehension of state utilities that there would be a flight of high-end consumers from their net, the non-availability of surplus power at reasonable rates, irrational open access charges, non-availability of open access infrastructure for metering, and segregation of consumers’ lines.

Although the regulatory commissions have promulgated regulations for open access, at times, discoms have their reservations. In the past few years, many states like Gujarat, Maharashtra, Rajasthan and Andhra Pradesh have allowed open access at a full-fledged level but have later backed off from promoting it on the ground that it had huge financial implications. In our view, the foremost reasons for the failure of open access are the huge cross-subsidisation level and the low collection efficiency for domestic and agricultural consumers. These reasons have been discussed below in detail.

Discoms discourage open access due to the cross-subsidisation level among various categories of consumers. The average billing rate (ABR) of some categories of consumers is below the average cost of supply (ACOS) of the distribution companies. Distribution companies cannot strive to supply electricity to consumers with a low ABR and at the same time allow their creamy consumers (that is, consumers paying higher than the ABR) to purchase power from other sources. This sensitive issue of a huge difference in the ABR and ACOS needs to be addressed at both the regulators’ and the government’s levels, as this would revive competition as enshrined in the Electricity Act, 2003.

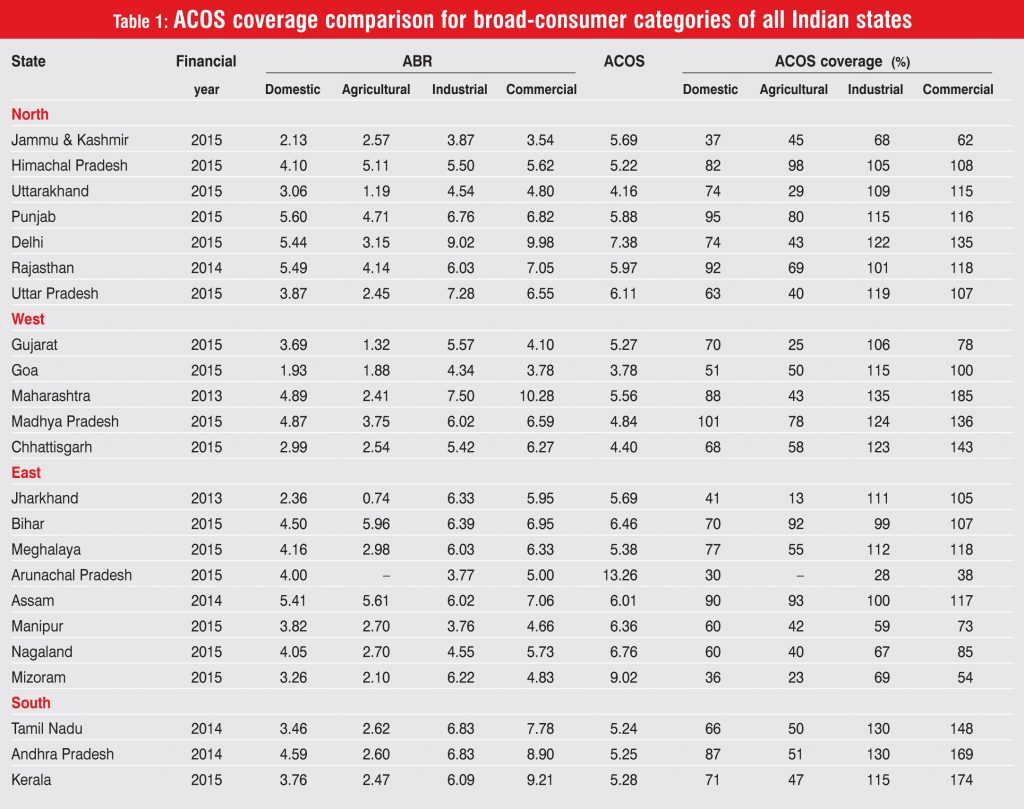

A study of the tariff orders of various states suggests that four broad consumer categories – domestic, agricultural, commercial and industrial – account for 80-90 per cent of the total energy sales for discoms (Table 1). It can be observed that the percentage of ABR to ACOS of the domestic and agricultural categories plays a significant role in the success or failure of open access. States like Maharashtra, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Punjab, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Andhra Pradesh, where open access has been allowed at a significant level, have balanced ACOS coverage, wherein the cross-subsidisation of agricultural and domestic consumers is far better than that in the other states, considering the inclusion of non-price factors (transmission and distribution capacity availability, metering infrastructure, etc.).

Further, the cross-subsidy surcharge (CSS) and additional surcharge for purchasing electricity from power exchanges and other sources were envisaged to be reduced over time as provided in the National Tariff Policy, 2006. However, over the years, the CSS has gone up.

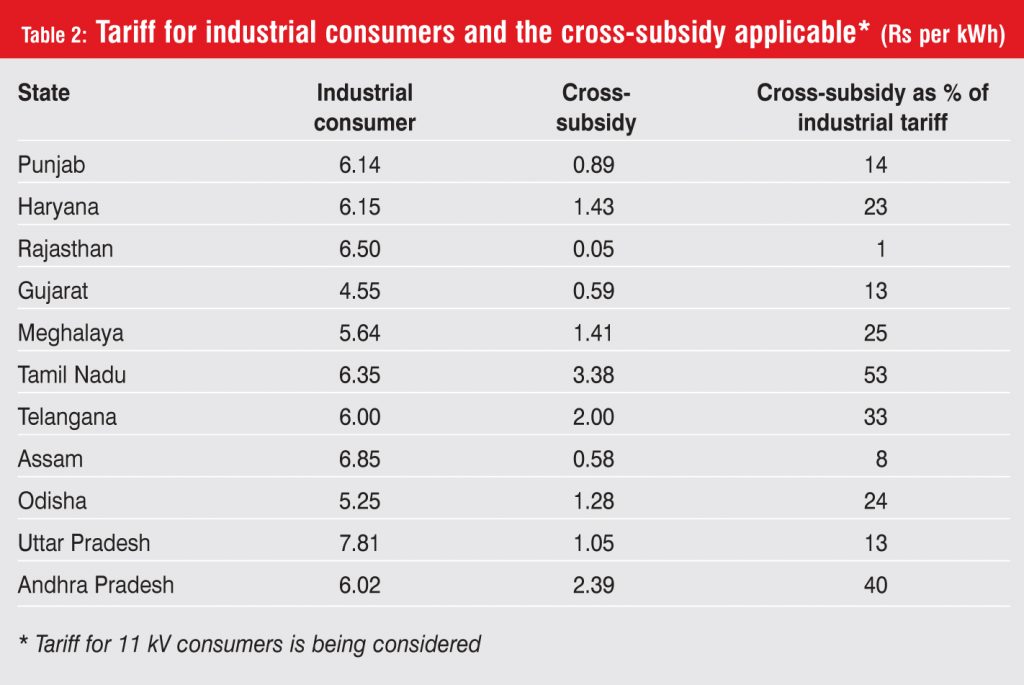

Currently, cross-subsidies of 20 per cent to 40 per cent are being levied, which denotes the extent to which industries are overpaying the reasonable cost of power, making it globally less competitive. Cross-subsidy will be gradually reduced as per the Electricity Act. Table 2 shows the industrial tariff and cross-subsidy level applicable in some states.

The collection efficiency of discoms is also one of the reasons for partial or non-allowance of open access to consumers. For example, high-end consumers or industrial consumers on an average have a minimum consumption of 1 MW or 720,000 kWh on a monthly basis, which amounts to an average billing of Rs 50 lakh per month from such consumers (considering Rs 7 per kWh as the electricity tariff for such consumers) and the collection from such consumers is always between 95 per cent and 100 per cent across the country, which contributes to the discoms’ revenue in a major way, whereas hundreds of consumers belonging to the other categories (domestic, non-domestic, etc.) that have a lower consumption of 100-2,000 kWh per month or more would be required by the discoms to generate the same amount of revenues. Also, the collection efficiency from such other categories of consumers is generally lower at 55-70 per cent. Thus, an industrial consumer with almost 95-100 per cent collection efficiency is much more lucrative for discoms for their effective financial performance.

The generation capacity addition programme as provided in the Twelfth Plan is likely to be achieved by almost 100 per cent and this will result in the availability of surplus power at all times of the day. In such a case, open access will facilitate the flow of power from surplus regions to deficit regions at market-determined rates. Further, the government’s vision of huge industrial production under the Make in India initiative, industries becoming internationally competitive, and the supply of 24×7 uninterrupted power to all sections of consumers can be realised through the effective implementation of open access across the country.

It must also be noted that to address the issue of CSS, the methodology for its computation needs to be reviewed and the ABR of different categories of consumers (domestic and agricultural) should be brought in line with the ACOS so that the CSS can be brought to an optimal level, thereby ensuring that power is being delivered at the real cost (along with overhead charges) to an open access consumer.

The open access market is typically driven by favourable end-user economics, so the regulators and the government need to put in sincere efforts to devise such a mechanism and address all the issues pertaining to open access and uninterrupted supply of electricity.