Flue gas desulphurisation (FGD) is one of the key technology solutions used at thermal power plants (TPPs) to cut down emissions. It helps in reducing suspended particulate matter (SPM) emissions along with sulphur oxide (SOx) emissions and is, therefore, given preference over other emission control systems. It has emerged as one of the key technology solutions to be adopted by TPPs to comply with the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change’s (MoEFCC) tightened emission norms issued in December 2015.

To help TPPs meet the FGD requirements, the Central Electricity Authority (CEA), along with regional power committees, drafted a plan last year for the phased implementation of FGD systems at plants with an aggregate coal-based capacity of 161 GW by 2022. Since then, FGD systems have been commissioned for about 1.8 GW of capacity, while the equipment market has seen heightened tendering activity, with a number of tenders issued/awarded in the last few months by a number of utilities.

Power Line takes a look at the progress in FGD installation by TPPs, recent policy developments as well as the challenges ahead…

FGD technology basics

FGD systems are required to be installed to treat the flue gas produced during fuel combustion in power plants, in order to scrub the constituent sulphur dioxide (SO2) before emitting it into the environment. The most widely used FGD technology is the wet-type FGD system. These are once-through systems and can be wet limestone based or seawater based.

Some of the other types of FGD systems are dry/semi-dry FGD (slaked lime based and quick lime based) systems and FGD systems based on proprietary technology such as ammonia, combined SOx-nitrogen oxide (NOx), non-thermal plasma and multi-pollutant control

The FGD technology solution best suited for a utility depends on a number of factors. These include the existing layout, ducting and space requirement for retrofitting; the nature and variation of fuel, flue gas composition and plant operating conditions; the percentage emission abatement necessary to meet the revised norms; source/intake, cost, availability, purity, reactivity and consumption of reagent; generation, quality, disposal/outfall, saleability and utilisation of by-products; existing plant water consumption and additional water requirement/treatment for FGD; and the life cycle cost comparison of feasible technologies.

However, some concern areas that will need to be looked at while installing FGD systems are the disposal, saleability and utilisation of by-products in the present and future scenarios. Waste water treatment and handling of water treatment rejects also need to be addressed.

Policy overview

As per the CEA’s revised FGD implementation plan, FGD systems are to be installed in the identified 161 GW of capacity by 2022. Around 350 units (128.7 GW) of the 414 units (161.4 GW) will complete the installation of FGD systems in 2021 and 2022. In recent months, there has also been significant ambiguity with regard to cost recovery on investments made in FGD systems. For instance, the CEA estimates the cost of wet limestone-based FGD to be around Rs 5 million per MW. Further, the tariff implication of FGD, considering an operational life of 15 years, auxiliary power consumption of 1.5 per cent and plant load factor of 62 per cent, is likely to be around Re 0.32 per kWh. In order to drive investment in emission control technology and address developers’ cost recovery concerns, the Ministry of Power (MoP) stated, in a letter to the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC) in June 2018, that investments in the installation of emission control technologies to ensure compliance with the MoEFCC’s December 2015 environmental norms would be treated as change in law events.

In another key development in the segment, in September 2018, the Supreme Court tightened the timelines for meeting the emission norms at 57 central sector thermal power units, requiring them to comply with the SOx and SPM norms by December 31, 2021. These include 48 units owned by NTPC Limited and nine owned by the Damodar Valley Corporation (while the deadline to limit NOx emissions remains unchanged at December 31, 2022). These plants comprise over 500 MW of capacity each and are located in highly polluted areas, with a population density of over 400 persons per square km.

Progress so far

Progress so far

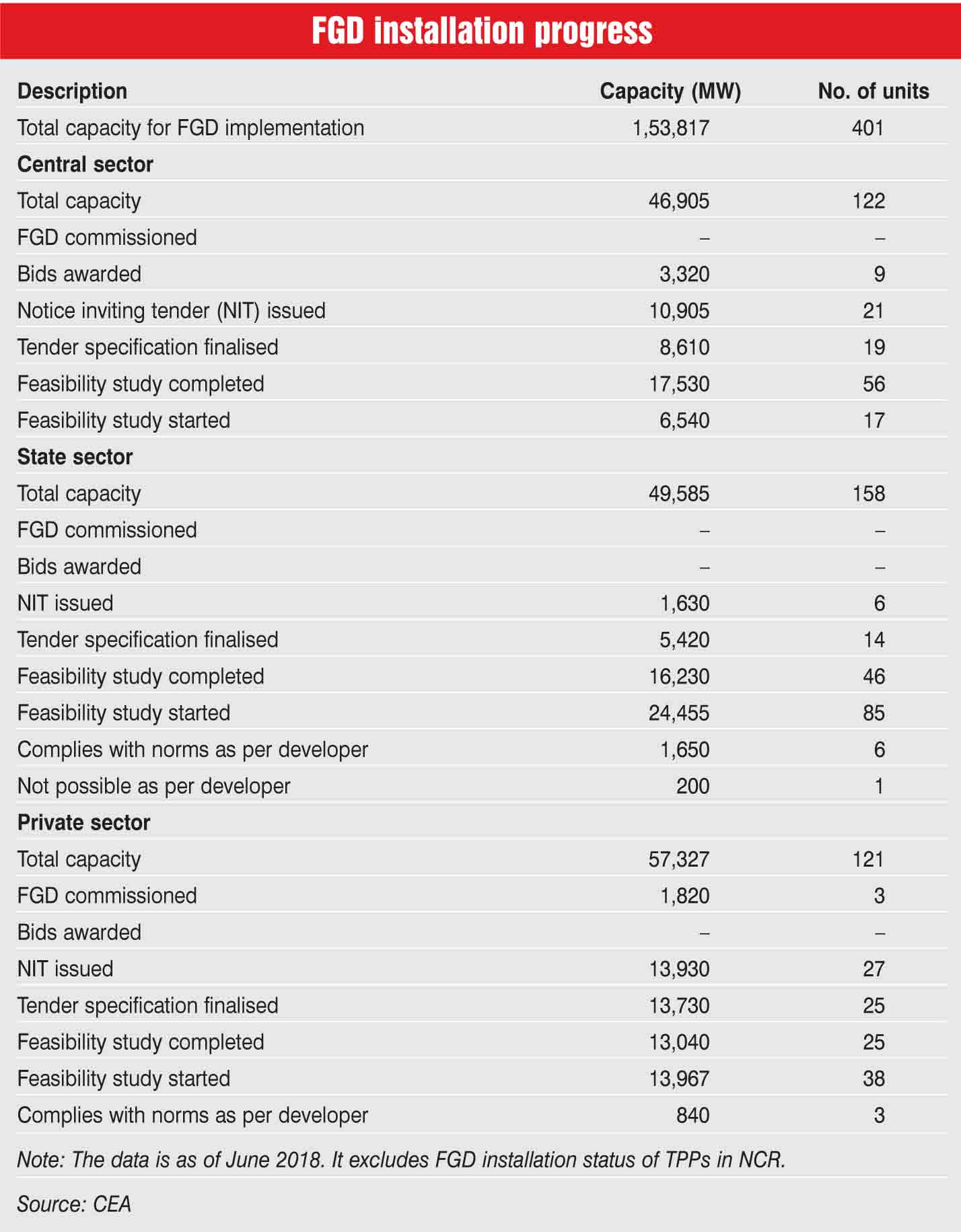

As per the CEA’s quarterly thermal renovation and modernisation (R&M) monitoring report for April-June 2018, FGD systems have been commissioned for 1,820 MW of capacity across three units in two private sector power plants – Tata Power’s 500 MW Trombay thermal power station (TPS) and CLP India’s 2×660 MW Mahatma Gandhi TPS (which is currently under R&M). Meanwhile, bids have been awarded for nine other thermal power units aggregating 3,320 MW of capacity, including NTPC’s 3×500 Indira Gandhi super thermal power plant (STPP) and 2×490 Dadri TPP.

Further, tenders have been issued for 26,465 MW of capacity across 54 units. Tender specifications have been finalised for another 27,760 MW of capacity across 58 units. Apart from this, feasibility studies has been completed for 127 units totalling 46,800 MW and feasibility studies have begun for 140 units totalling 44,962 MW.

Recent tenders

Recent tenders

With regard to the key equipment providers for FGD systems in the country, Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited (BHEL) has emerged as the front runner. As of October 2018, the company has secured FGD orders for 32 units from various customers, with the latest one being a Rs 29 billion order from NTPC Limited for the supply and installation of FGD systems at the 3×660 MW North Karanpura, 2×500 MW Mauda Stage I, 3×660 MW Barh Stage I and 2×660 MW Barh Stage II power projects. Besides this, Larsen & Toubro (L&T) secured a Rs 14 billion order in September 2018 for implementing FGD systems at NTPC’s Vindhyachal STPP in Madhya Pradesh and Darlipali STPP in Odisha, and another Rs 10.8 billion order, secured in August 2018, for NTPC’s Khargone STPP in Madhya Pradesh and Lara STPP in Chhattisgarh.

Reliance Infrastructure Limited also recently secured an engineering, procurement and construction contract worth Rs 5.67 billion from NTPC for carrying out FGD works at the latter’s 1,500 MW Jhajjar coal-based power plant in Haryana.

Also, ISGEC Heavy Engineering emerged as the L1 bidder in the reverse auction for the supply of FGD systems for three units of 800 MW each of NTPC’s Kudgi STPP in July 2018. GE Power received its first stand-alone order of Rs 3.09 billion from NTPC Limited for installing FGD technology at Phase I (2×800 MW) of NTPC’s STPP in Telangana in March 2018.

Notably, domestic equipment providers have partnered with global firms for developing FGD technology in the country. While BHEL has collaborated with Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems, Japan, L&T has collaborated with Japan’s Chiyoda Corporation.

Issues and concerns

With regard to the timeline for ensuring compliance with the emission norms, the Supreme Court has criticised the MoP’s extension in the deadline from December 2017 to December 2022, stating that this reflects a lack of seriousness. Further, in September 2018, the court issued notices to the state-owned power generating companies and association of power generating units to apprise it of the time needed for complying with the emission norms. On October 11, 2018, the court granted an additional four weeks’ time to generating companies to submit their response to the court, following a request for the same.

Meanwhile, since banks and financial institutions are reluctant to fund projects owing to the stress in the sector and the exhaustion of their lending limits to the power sector, the Association of Power Producers (APP) has written to the MoP seeking to bring in the Power Finance Corporation and the Rural Electrification Corporation to provide funds for implementing emission control systems. Besides this, the APP has asked the ministry for the application of ad hoc additional tariffs from the date of installation of the system while the adjustment in tariff (along with interest payments) could be undertaken following the finalisation of tariffs by the electricity regulatory commissions. Besides this, the APP has sought directions from the ministry for scrutinising and approving the feasibility studies and detailed project reports on its own, rather than routing the approval process through the regulatory commissions.

The way forward

The way forward

Undoubtedly, in recent months, significant progress has been seen with regard to the ordering activity for the installation of FGD systems at power plants. Besides, allowing the pass-through of investments made in FGD systems has been a big positive for the sector. However, a few challenges continue to hamper the smooth implementation of FGD systems, with the lack of space and insufficient time being the key concerns. A number of units do not have the space to install an FGD system, which makes it difficult for such units to comply with the emission norms. In the case of units that have space available, it takes almost three years for the pre-implementation work.

That said, the coming months are expected to witness significant momentum with regard to ordering activity for FGD systems. With the Supreme Court seeking timelines from the gencos for complying with the emission norms, timely completion of FGD projects is expected in the coming years.