Compliance with the revised emission norms issued by the environment ministry in December 2015 remains tardy, and the industry has been seeking an extension to the 2022 deadline. The Ministry of Power (MoP) recently wrote to the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) on the issue, and it is expected that a two-year extension will be provided to a majority of coal- and lignite-based thermal power plants (TPPs) for the installation of emission control equipment.

Flue gas desulphurisation (FGD) systems are to be deployed by 448 thermal units, aggregating over 169 GW, in a phased manner by 2022. Meanwhile, electrostatic precipitators (ESPs) are to be installed in 220 units, totalling 63.4 GW. As of June 2020, only four units, totalling 1,740 MW or just about 1 per cent of the targeted capacity, have commissioned FGDs. However, FGD tenders have been issued for 120 GW of capacity and bids have been awarded for 56.8 GW. The MoP has, reportedly, sought an extension of the deadline up to 2024 for 322 units aggregating 100 GW. It is expected that a uniform two-year extension may not be provided to all identified TPPs, but a relaxation would be granted depending on the progress made by each plant in completing FGD installation.

In addition, a recent report by the Central Electricity Authority (CEA) suggests that TPPs can install emission control equipment in phases, with immediate installation required only in areas with high levels of sulphur dioxide. The areas with lower concentrations of the pollutant may not require emission control equipment in the near future. Power Line takes a look at some of the recent developments and challenges in the installation of emission control systems…

Plant-location specific emission standards

The CEA has recently released a paper on plant location specific emission standards, according to which the ambient air quality (AQI) can be made the guiding factor for formulating a schedule of implementation of emission control equipment.

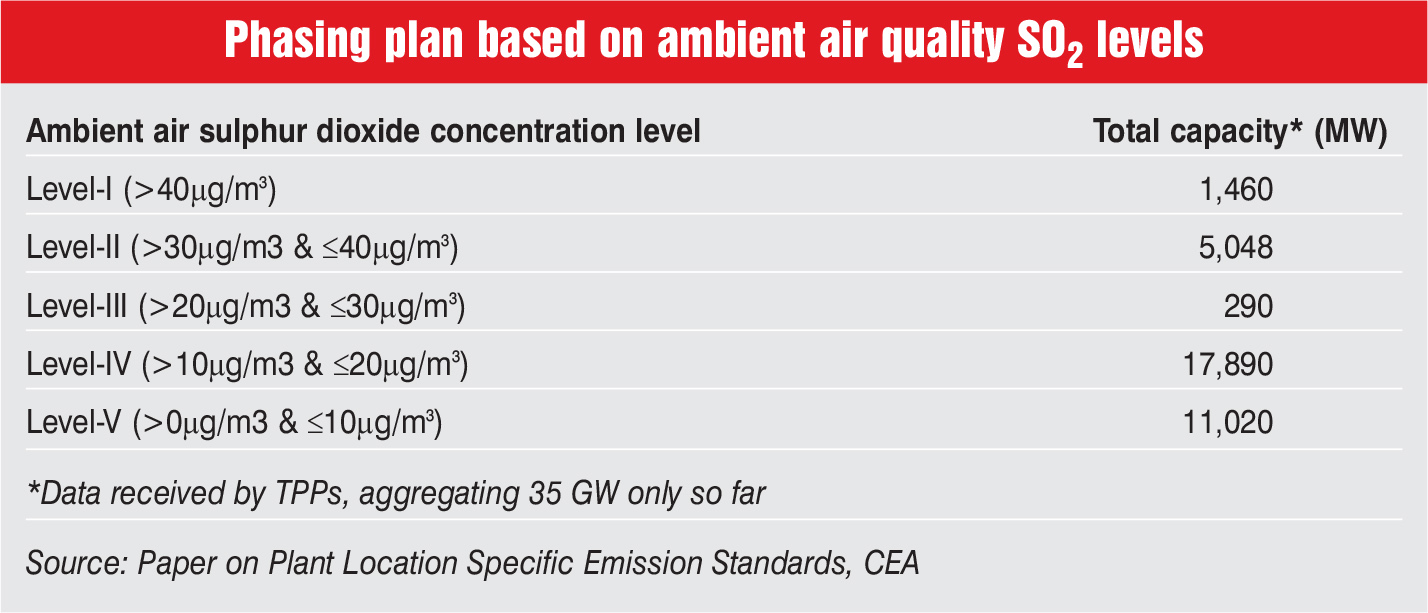

As per satellite imagery reports, sulphur dioxide concentrations seem to be high in clusters in the states of Odisha, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Gujarat. Accordingly, the CEA recommends that the installation of emission control equipment in TPPs should be carried out in a graded manner, starting with those located near the most affected cities/areas, where ambient sulphur dioxide levels are the highest. On the basis of data received from power stations aggregating over 35 GW, AQI has been divided into levels or phases according to the presence of sulphur dioxide. The thermal power capacity has been correspondingly divided into various levels (see Table).

It is recommended that in the first phase, emission control equipment should be installed in areas where sulphur dioxide levels are higher than 40mg per m3 (Level I). About 1,460 MW of capacity falls in this level at present (although data has not been received from all TPPs). Subsequently, a year after the completion of the first phase and upon analysing the effectiveness of the control equipment, plants located in areas where ambient sulphur dioxide levels are higher than 30mg per m3 (Level II) can take up FGD installation. Meanwhile, TPPs located in areas where ambient sulphur dioxide levels are lower than 30mg per m3 (Levels III, VI and V) need not take any corrective measures at present.

NOx norms update

In July 2020, the Supreme Court allowed the relaxation of NOx norms for TPPs installed between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2016 from 300 mg per Nm3 to 450 mg per Nm3. The MoP had proposed revising the norms as TPPs were unable to meet the existing limit (of 300 mg per Nm3 and below) at varying load conditions. The Central Pollution Control Board monitored emissions at seven of NTPC’s power plants for a specific period and the results were found to be in line with the MoP’s observations.

As per NTPC’s pilot projects, it has been found that combustion modification can help reduce NOx from around 750 mg per Nm3 to around 450 mg per Nm3. For selective non-catalytic reduction (SNCR) technology, NOx reduction is in the range of 20 per cent to 30 per cent. Further, it was found that while a reduction in NOx of around 80 per cent is achievable, it is not consistent due to part load operation of power plants.

With the change in NOx limits, TPPs commissioned between 2004 and 2006 will not be required to implement advanced DeNOx technologies such as selective catalytic reduction (SCR) or SNCR as an NOx emission level of 450 mg per Nm3 can be achieved through combustion modification. NOx reduction technologies such as advanced burner technology, along with advanced air supply systems such as separated over fire air (SOFA) technology, can help utilities meet the emission norms. This will not only reduce emissions more efficiently, but will also improve plant performance by enabling more stable and reliable operation.

Issues and challenges

Gencos have flagged several issues and challenges in the implementation of emission control systems, particularly FGDs. For instance, although the MoP has issued directions to treat the requirement of FGD installation as a change in law event and pass on the costs, and the CERC has passed favourable orders on a case-to-case basis, these orders are being challenged by discoms. Without prior approval from the regulators, lenders are unwilling to finance FGDs in view of uncertainties regarding cost recovery. The CERC has issued a staff paper regarding compensation to gencos for the installation of emission control systems, but a final order/regulation on the subject is still pending.

In addition, the recent restrictions on import of power equipment from China have affected many TPPs that had already finalised tender or started procurement from Chinese companies. As a result, many of these tenders have now been scrapped, and selecting new vendors will take time. For instance, the Haryana government has cancelled two FGD contracts awarded to Chinese companies through the international competitive bidding (ICB) route by Haryana Power Generation Corporation Limited. The contract for the Deen Bandhu Chhotu Ram TPS in Yamunanagar was awarded to Beijing SPC Environment Protection Tech, and the one for the Rajiv Gandhi TPP in Hisar was awarded to Shanghai Electric Corporation. Now, HPGCL plans to invite fresh tenders for FGDs, limiting participation to only domestic companies. Similarly, Maharashtra State Power Generation Company Limited has cancelled the tender for FGD installation for its Koradi TPP.

In addition, for plants without PPAs, many of which are under financial stress, there is little clarity regarding how they would be compensated for FGD costs. There is also a need to devise a mechanism for cost recovery for TPPs selling power through power exchanges or under short-term contracts.

Captive power plants are facing even greater challenges, as industries cannot pass on the escalated cost burden to end-consumers as prices of most of the products are market-linked. A high capex/opex (Rs 500 million-Rs 700 million per MW of capital investment) is required for FGDs, which increases electricity generation costs and, in turn, affects industrial production costs. Moreover, most industries had set up CPPs without planning for space for installing FGDs and, therefore, they need more time to identify new land following techno-feasibility studies.

The way forward

The installation of emission control equipment in existing TPPs is undoubtedly challenging and with greater integration of renewables, thermal gencos are already facing the heat in terms of low load operation and flexibilisation requirements. However, this does not undermine the fact that TPPs need to cap their emissions and contribute to a more sustainable environment. While policymakers need to take steps to resolve issues faced by the thermal power industry, a blanket extension of the deadline to implement emission control solutions may not send the right signals and may encourage complacency on the part of gencos. In this context, the CEA’s recently recommended phasing approach can be adopted, as it will help in understanding the impact and effectiveness of emission control equipment while providing time for future course corrections.

Neha Bhatnagar