Data centres require a large amount of electricity for storing, processing and networking data in addition to cooling the servers from overheating. Electricity for HVAC and power provision systems is the biggest component of the operational cost of a data centre, accounting for a 45-50 per cent share. Hence, the expansion of the data centre market will be accompanied by an increase in power consumption.

Electricity cost in the capex and opex of data centres

Electrical and cooling systems account for the largest share of almost 70 per cent of construction costs in data centres compared to commercial establishments, which account for around 15 per cent. The cost of operating and maintaining data centres is the major component of their cost structure. The annual operating cost of data centres with a capacity of 1 MW ranges from $5.4 million to $27 million depending on the size of the data centre. In general, economies of scale are a major factor in determining the cost of operation as increasing the size of data centres by tenfold led to a decrease in operational costs by as much as 129 per cent.

The operational cost of a data centre consists of the cost of electricity for processing and storing data, cost of power for HVAC systems, cost of employing technical staff, leasing cost, and networking and compliance costs. Among these operational cost factors, electricity for HVAC and power provision systems is the biggest component, accounting for 45-50 per cent of the operational expenditure.

The annual operational expenditure of a data centre, constituting 55-70 per cent of the total expenditure, exceeds its capital cost. Therefore, it is imperative to focus on enhancing the operational efficiency of data centres.

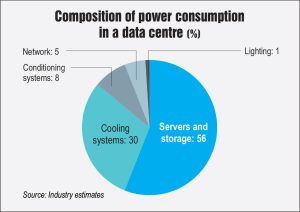

Power is consumed by various subsystems comprising servers and storage systems, power conditioning equipment, cooling and humidification systems, networking equipment and lighting as well as physical security. Servers and storage systems and HVAC systems account for 56 per cent and 30 per cent of power consumption respectively. Power conditioning, that is, backup power and network-related power consumption accounts for 8 per cent and 5 per cent of consumption respectively with lighting accounting for the remaining quantum. Thus, electricity needs to be procured at a low cost and used in an efficient way so that the commercial viability of data centres improves significantly. The efficiency of power consumption in data centres is measured by power usage effectiveness (PUE) signifying the quantum of power consumed by IT equipment vis-à-vis total data centre power consumption. Efficient plants have a PUE of 1.2, of which auxiliary power consumption accounts for 0.2 while the rest of it is used for IT equipment.

Sources of power procurement

The cost of electricity procurement is dependent on the location of the data centre, the business model used for power procurement and the subsidies and incentives provided by the state and central governments. Data centres can either source power from discoms through open access, or generate electricity via captive installations (mostly renewables), or procure electricity from the grid via discoms and captive sources, that is, the hybrid model, depending on availability and cost.

Grid: Sourcing power from the grid ensures reliability and consistency, which is essential for data centres. Moreover, discoms can supply dual power that is, power from two different grids and different generation units, to data centres in case the sanctioned load is greater than 50 MW. Dual power helps in further improving the reliability of supply. Discoms are also ready to install an additional feeder (direct supply) for data centres if the sanctioned load of a data centre is more than 100 MW. Certain discoms are also ready to augment and upgrade the supply of power by 50 per cent depending on the requirement.

City grids or community grids will not only solve the issues of harmonics, voltage sag, frequency variations and momentary outages (enough to trip expensive servers and computers), but stable and reliable supply will also result in significant long-term operational cost savings, improve equipment reliability and augment the life of the components.

From a cost perspective, the cost of power procurement from the grid is considerably low in most Indian states in comparison to other countries at $0.08-$0.14 per unit according to a NASSCOM report. In addition, several state governments such as the Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu governments extend subsidies on electricity duty, electricity tariff, etc. to data centres, recognising the importance of their installation. However, the disadvantage of depending on the grid for power is that the cost of procuring electricity can rise year on year depending on the fuel cost, making it difficult to conduct long-term planning. Moreover, hyperscale data centres such as AWS and Google find it commercially more viable to generate and rely on on-site power given their large capacities.

Captive generation (on-site): Data centres around the world require more high quality power than energy grids can supply. Fluctuations in power supply can lead to lengthy periods of downtime, and many data centres now turn to on-site power generation as a solution to this problem. In a more fundamental sense, captive generation enables companies to generate electricity and significantly reduce their expenditure on power procurement. These captive installations are also more resilient as they operate even in case of grid-related contingencies.

Captive generation gives the data centre greater control on energy supply, ensuring better consistency and uptime. Captive generation improves energy efficiency and reduces transmission line losses as the captive installation is situated close to the data centre. Both these factors reduce power procurement costs and by extension the operational costs of data centres.

Installing renewable captive capacity such as rooftop solar, wind-based power and hybrid-solar plants also ensures that data centres are sustainable. Developing captive capacity insulates data centres from rising price pressures and helps them generate more revenue by selling surplus power back to the grid. Nonetheless, the intermittency risk and the slow ramping rate of renewable installations such as solar and wind constrain their adoption. Moreover, several companies are opting to rely on hybrid cloud or in-house cloud capacities that are considerably smaller than hyperscale data centres. Thus, it is commercially unviable to incur the exorbitant upfront capital cost of developing a small captive capacity for them. Also, data centres based on captive power will have to independently undertake the task of expanding their generation capacity while planning their expansion, raising their upfront capital costs significantly compared to grid-based data centres.

In recent years, Yotta Infrastructure, backed by the Hiranandani Group, commissioned a data centre park in Noida with a captive solar power plant and a natural gas-based cogen power plant. In 2021, Bharati Airtel commissioned a 14 MW captive solar power plant in Uttar Pradesh to meet the energy requirements of its core and edge data centres in the state. Similarly, NTT Data, the world’s third largest data centre operator, has also ramped up its green energy capability by setting up solar and wind captive renewable energy plants across the country. It has already set up 62.5 MW of capacity (solar) in Maharashtra and 20 MW (wind and solar) in Karnataka. NTT Data is looking to augment this capability by another 100 MW by setting up a plant in Maharashtra. According to a report by CRISIL Limited, the share of renewables in India’s data centre power consumption currently stands at around 15 per cent and is projected to rise to 35-40 per cent by 2024-25. This shift to cheaper renewable power is estimated to augment the operating margins of data centres by 2-3 per cent by 2024-25.

In recent years, Yotta Infrastructure, backed by the Hiranandani Group, commissioned a data centre park in Noida with a captive solar power plant and a natural gas-based cogen power plant. In 2021, Bharati Airtel commissioned a 14 MW captive solar power plant in Uttar Pradesh to meet the energy requirements of its core and edge data centres in the state. Similarly, NTT Data, the world’s third largest data centre operator, has also ramped up its green energy capability by setting up solar and wind captive renewable energy plants across the country. It has already set up 62.5 MW of capacity (solar) in Maharashtra and 20 MW (wind and solar) in Karnataka. NTT Data is looking to augment this capability by another 100 MW by setting up a plant in Maharashtra. According to a report by CRISIL Limited, the share of renewables in India’s data centre power consumption currently stands at around 15 per cent and is projected to rise to 35-40 per cent by 2024-25. This shift to cheaper renewable power is estimated to augment the operating margins of data centres by 2-3 per cent by 2024-25.

The way forward

India’s data centre capacity is projected by ICRA to grow at 18-19 per cent CAGR in the next two years to around 1,200 MW by 2024 with an increase in rack capacity utilisation as well as installation of data centres. Furthermore, in the medium term, India’s data centre market is set to grow almost fivefold to 3,900-4,100 MW on the back of a substantial investment of Rs 1 trillion-Rs 1.05 trillion.

The growth of data centres in India will be accelerated by localisation rules; better commercial viability; exponential rise in data storage; data consumption and data processing, and emerging technologies such as IoT and 5G. Currently, electricity accounts for 45-50 per cent of the operational cost of data centres. However, it can be reduced significantly, conditional to investment by data centres in developing captive renewable energy capacity. Therefore, it is vital that the government, hyperscalers, data centre clients and other industry stakeholders collaborate to set up greater captive capacity for data centres. It will also make the deployment of data centres in India more attractive for foreign investors.