The small-hydro power (SHP) industry has experienced limited growth over the past one year, but a strong debate over a government proposal has brought the segment back into the limelight. The government is mulling over bringing large hydropower projects, of over 25 MW capacity, under the ambit of renewable energy by clubbing them together with SHP projects (of less than 25 MW capacity). The difference between the two is that while SHP projects do not require the construction of a dam, large hydro projects typically require a dam.

The SHP segment has been continuously underperforming, missing or barely meeting its targets over the past few years. Investor interest in the segment has dampened due to high investments, low tariffs and low returns because of insufficient rains, which restrict power generation and hence, revenues. Of the estimated potential of 20,000 MW, only about 22 per cent has been developed so far. The National Mission on Small Hydro, which was launched by the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) in 2015, failed to find many takers for SHP projects. Even though the mission aims at reviving the segment through increased budgets and research and development, falling tariffs and increasing costs have created an unfavourable environment for its growth.

Current status

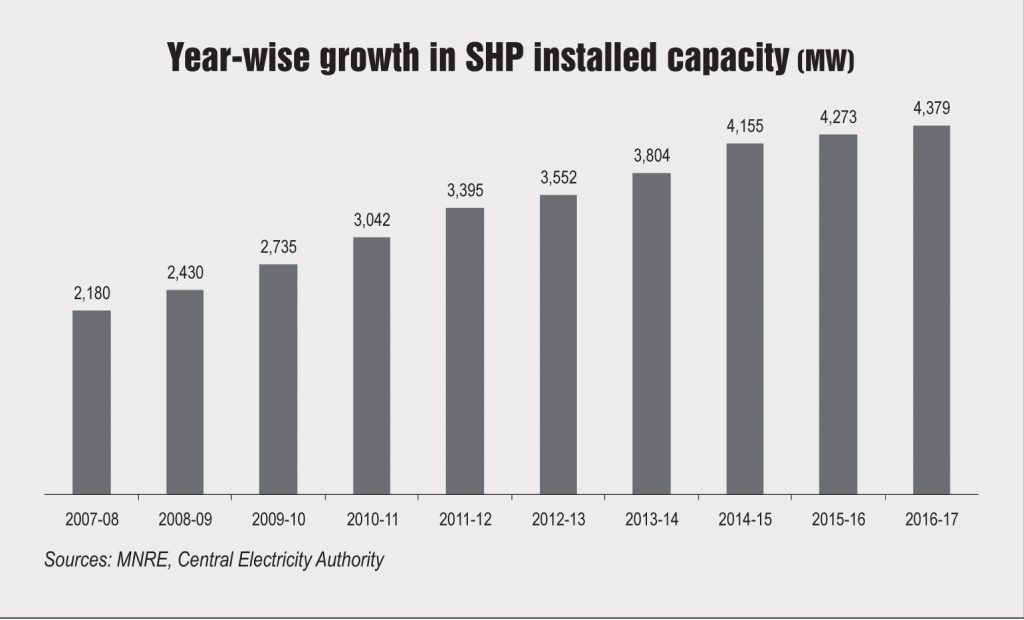

As of March 2017, the country’s cumulative installed SHP capacity stood at 4,379.85 MW across 1,077 sites. About 106 MW of SHP capacity was added in the previous financial year as against a target of 250 MW. Currently, 24 of the 29 states have policies in place to promote SHP, but most of them lack the potential for SHP development.

The highest potential has been identified in Karnataka, at nearly 4,141.12 MW, of which 1,220.73 MW has already been installed across 166 sites (as of December 2016). The state has the highest share of capacity in the country at 28 per cent, followed at a distance by Himachal Pradesh at 18 per cent. Himachal Pradesh has an identified SHP potential of 2,397.91 MW and an installed capacity of 798.8 MW. Maharashtra has the third largest installed capacity of 346.17 MW or nearly 8 per cent of the total installed capacity; its potential, however, is lower than that of many other states.

Proposed policy changes

The government is in the process of making some policy changes in order to revive investor interest in this space. Recently, it floated a draft policy to generate interest among developers through the process of competitive tariff bidding for the allocation of SHP projects.

Water is a state subject and therefore requires the approval of the states for the SHP tariff structure. The fixed tariffs have been declining, thereby leaving developers in a difficult situation owing to low returns. With competitive tariff bidding, developers are expected to give their own tariff rates to win contracts. However, according to developers, the state administrations could possibly cap the tariffs, which would make the exercise redundant. The Jharkhand Renewable Energy Development Agency released a request for proposal in September 2016 for project allocation through competitive bidding for 13 plants with a total capacity of 125.2 MW, marking a sharp deviation from the usual tendering process. The last date for receiving bids was recently extended to May 26, 2017.

Inclusion of large hydro

The government has proposed to change its definition of renewable energy sources to include large hydropower projects. The proposal, which is at initial stages of discussion, was floated in January 2016 and has found both proponents and opponents in the industry. On the one hand, it is being seen as a boon for the hydropower segment as it would immediately provide financial benefits to the highly cost-intensive projects. On the other hand, the opposing faction, comprising mostly environmentalists, argues that hydropower plants are not net zero-carbon projects as they require the construction of dams, which is a carbon-intensive process.

The government’s ambitious renewable energy target of 175 GW by 2022 is being seen as the main driver for the inclusion of large hydropower projects. As of March 2017, 44.5 GW of large hydropower capacity was installed while renewable power capacity stood at 57.26 GW. Including large hydro under the ambit of renewable energy would dramatically increase the installed renewable energy capacity and bring the country closer to achieving its targets. Given that India has also ratified the Paris Agreement, its responsibility to meet the targets to reduce its dependence on fossil fuels increases.

Although power generation from large hydro plants does not emit any greenhouse gases, experts are of the opinion that these projects do not provide the benefits that define renewable sources of energy. Dams have to be constructed for power generation, which is harmful to the ecosystem. In addition, marine life and water supply to farmlands are adversely affected. Since the projects are capital intensive, the budget allocated for other renewable energy sources could be diverted to fund hydropower projects. These factors together contribute to the vulnerability of climate change, working against the essence of renewable energy.

Challenges

The restricted growth of SHP can be attributed to multiple issues. While some of the challenges are technical, most are policy-based problems that need to be resolved at the state and central levels. The gestation period for SHP projects is much higher than that for their counterparts. Although actual plant construction takes only around two years, developing the entire project takes four to eight years, most of which time is spent in getting clearances from various agencies from the centre to the state to the local authorities. This discourages developers from entering the segment. Uncertainties related to rainfall and the lack of proper weather forecasts have also constrained the growth of the SHP segment.

Power evacuation is another concern among developers, who often incur losses due to the unavailability of the grid network for power transmission. To this end, SHP project owners are often asked to curtail generation, resulting in revenue loss and suboptimal usage of the plant. A common issue faced during all new renewable installations will be resolved with the expansion of the power grid to accommodate the upcoming renewable energy capacity.

SHP tariffs have been decreasing steadily with most states offering less than Rs 5 per kWh, while the capital cost of SHPs has increased in recent years. As per industry sources, the capital cost of an SHP plant in hilly areas has increased by almost 60-70 per cent in the past five years and ranges from Rs 110 million to Rs 120 million per MW. Of all the states with tariff policies in place for SHP, Karnataka has one of the highest tariffs, at Rs 4.45 to Rs 5.25 per kWh. This has resulted in considerable growth. However, Maharashtra has the widest range of tariffs for different capacities, ranging from Rs 4.08 for a capacity of 5-25 MW to Rs 5.75 for less than 500 kW of capacity. It also has the highest tariffs among all states, resulting in high SHP adoption in the state.

The government’s proposal to bring in tariff-based competitive bidding for SHP projects is expected to considerably increase the growth momentum in the segment. The government is in the process of finalising the norms for the implementation of the same. This process could help eliminate the challenges associated with the segment as it would encourage developers to provide their own tariffs to win projects.

Future prospects

With the government’s proposal to merge small and large hydro projects, the SHP segment may not exist as a separate entity in the near future. In that case, the targets would change and so would the policies governing SHP projects, which could lead to renewed interest in projects with a capacity of less than 25 MW. Further, the future of competitive bidding seems uncertain, as it has not found much appreciation among developers. However, since the results of the first tender are yet to be seen, it cannot be completely written off. For the SHP segment to take off, reform policies under the National Mission on Small Hydro need to be introduced to push up tariffs and generate returns for developers.