One of the key comments in this year’s Economic Survey was regarding aggressive bidding in the coal block auctions. “In the case of spectrum, coal and renewables, auctions may have led to a winner’s curse, whereby firms overbid for assets, leading to adverse consequences in each of the sectors,” it stated.

Among the most crucial events in the timeline of India’s coal industry was the cancellation of captive coal mining blocks by the Supreme Court in 2014. What followed was a swift policy action plan to overhaul the allocation policy framework by introducing a competitive e-auction method whereby end consumers were required to bid for coal blocks. Since December 2014, five rounds of auctions have been announced, with 30-odd blocks (of the 204 cancelled blocks) being auctioned so far.

While this was meant to resolve the prevailing challenges and boost output, the segment today faces significant pressure, as the survey points out. The players’ exuberance led them to bid aggressively for blocks, which have today become unviable. The government’s decision to disallow pass-through of the quoted discount price after the bidding was over came as another major setback. The fallout is that the winning bidders are now surrendering their assets or struggling to bring their coal mines into operation. The most recent case in point is Essar Power, which submitted a request for surrendering its Jharkhand mine in January 2018.

Further, production, which was expected to increase from the reallocated blocks, has failed to ramp up. There has been a distinct lack of interest from bidders in the subsequent rounds of auctions; in fact, the last two rounds had to be cancelled owing to tepid response from the industry. The macro scenario has also changed significantly since then, with domestic supply being ramped up and international coal prices crashing, making it cheaper to source coal from overseas. Moreover, power demand by discoms fell, which meant that coal-based plants sat on idle capacity, drastically reducing their coal requirements.

There is also not much clarity on the future bidding rounds. In fact, a recent draft report by consultancy firm KPMG, titled “Coal Vision 2030”, forecasts that no new mines will be required beyond those already allocated or already auctioned off.

While the captive coal mining industry is in a flux, the government has recently given its approval for auctioning commercial coal blocks to private players (see box). The move has brought cheer to the industry, as this would break the monopoly of Coal India Limited (CIL) and usher in the much-needed competition in the sector, which has been nationalised since 1973.

What has been the performance of the captive coal mining segment so far? What are the challenges for the segment and the future outlook? Power Line takes a look…

Dwindling production

To recap, in September 2014, the Supreme Court ordered the deallocation of 204 of the 218 captive coal blocks that had been allocated between 1993 and 2011, terming the allotment as “illegal” and “arbitrary”. In October 2014, the government notified the Coal Mines (Special Provisions) Ordinance, 2014 for management and reallocation of the cancelled coal blocks.

In December 2014, the Ministry of Coal commenced the process for coal block auctions as well as allotments to government companies (through nominations). Since then, 84 blocks have been reallocated, which includes 31 mines through auctions and 53 mines to government companies through nomination.

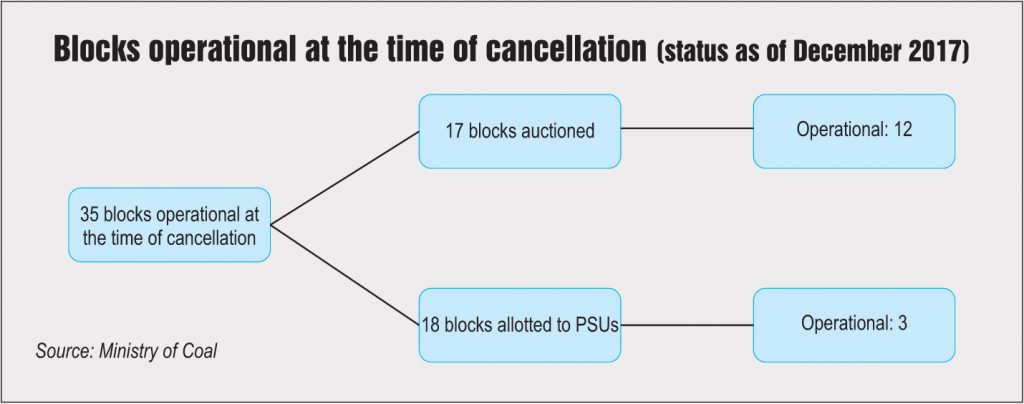

Of the blocks reallocated, 35 belong to the Schedule II category. (As per the government’s classification, Schedule II blocks are the ones that were operational or on the verge of producing coal at the time of the cancellation.) Of these 35 blocks, 17 mines were auctioned and 18 mines were allotted to government companies.

As per the coal ministry’s data, only 15 of the 35 mines (42 per cent) have resumed mining since then. The other mines are yet to be operationalised due to legal issues or lack of green clearances.

The total captive coal production stood at 37.43 million tonnes (mt) in 2016-17. The auctioned/alloted blocks produced 15.3 mt in 2016-17 as compared to 15.8 mt in the period prior to the cancellation of allocation of these mines. Prior to the Supreme Court’s cancellation decision, there were about 40 mines that were producing close to 52 mt in 2014-15. Observers note that even in the blocks that are producing, production has been kept at the bare minimum in order to avoid penalties.

Winner’s curse for the power sector

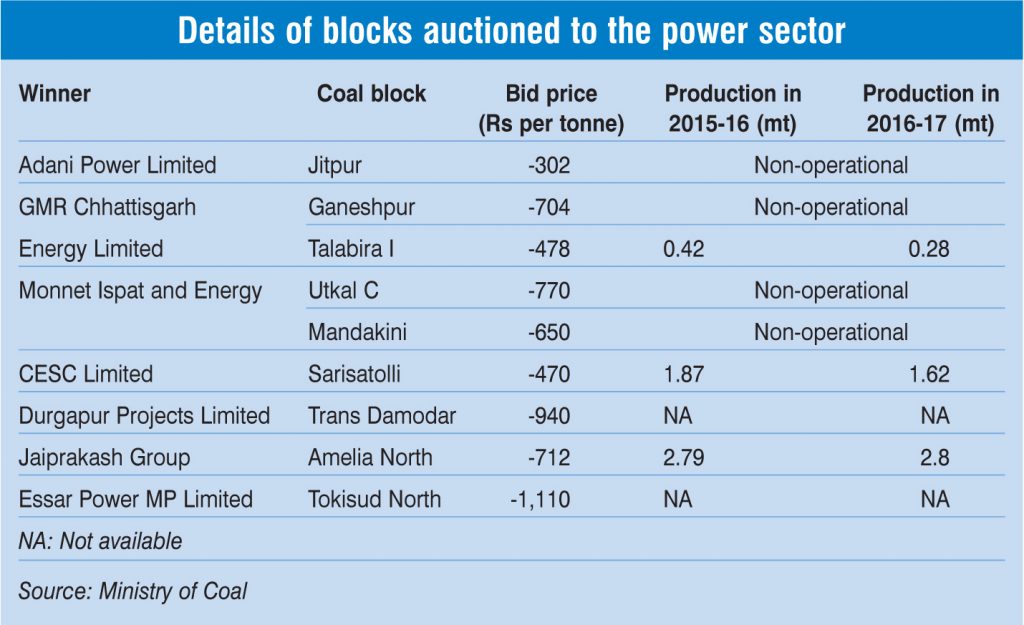

The coal blocks earmarked for the power sector were awarded through reverse auction, where the winning bidder was the one that quoted the lowest transfer price of coal. In negative bidding, power producers that seek to win captive coal blocks have to give up their right to pass on the mining costs to consumers and instead, agree to pay the government an additional premium.

However, in order to restrict the amount of mining cost that could be loaded on to the consumer, the government capped the fixed charge, thus inhibiting companies from recovering their entire cost. “The possibility of camouflaging fuel cost as capacity charge has been plugged through the regulatory cap. With little scope for such financial jugglery, the coal block winners have had a tough time securing finances for coal mining and investors have been wary of these projects,” says Dipesh Dipu, managing partner, Jenissi Management Consultants.

Overall, eight power companies won coal blocks by making negative bids. These were CESC, GMR Energy, Durgapur Projects Limited, Essar Power, Jaiprakash Power Ventures Limited, Jindal Power, Adani Power and Monnet. Most of them have reportedly moved court to challenge the government’s decision to disallow pass-through of the quoted discount on coal cost in the final power tariff.

Also, with uncertainty on coal cost recovery, the winners became reluctant to proceed with coal block operations. Earlier, in 2015, Mandakini Exploration and Mining (a joint venture between Jindal India Thermal Power and Monnet Ispat), which won the Mandakini coal block in Odisha, and Monnet Power Company, which won the Utkal C block in Odisha, had approached the court to surrender their coal blocks on grounds of unviability.

Now Essar Power has submitted a request for its Tokisud North coal block in Jharkhand. The company has reportedly invested close to Rs 4.9 billion in the block, which is linked to its 1,200 MW Mahan power project. The company says that the block needs an additional Rs 6 billion of investments. It has moved the Delhi High Court seeking a refund of the investment made in the block till date. The block was won by the company in February 2015, quoting an unprecedented negative bid of Rs 1,110 per tonne for the Tokisud North block.

That the auction process was flawed seems to be the primary reason for the sector’s mess. “The system was designed for scenarios of zero cost and additional premium, which are beyond comprehension if economic prudence is considered,” says Dipu.

The outcomes would have been better if instead of the cost of mining, the cost of power generation had been used as the bidding criterion. “Tariff-based competitive bidding processes are not new and are well known. Case 2 bids, with the coal block specified, could have quite easily fit the bill for auctions,” Dipu adds.

Outlook

The impact of low production from captive blocks has not been significant with domestic coal consumption being subdued and there being oversupply in the coal market. CIL has had record production in recent years, of 536 mt in 2015-16 and almost 554 mt in 2016-17. With power demand tapering, CIL has also started building a huge inventory.

Another significant challenge for the captive coal block segment is the cost competition from cheaper alternative sources of coal. According to KPMG’s estimates, the landed cost of coal from alternative sources is less than coal from a number of allocated captive coal blocks (35-40 per cent of the blocks allocated till date). As a result, these blocks are likely to face constraints in production.

The timeline for future bidding rounds is still uncertain. By the fourth and fifth rounds of auctions, interest had fallen drastically, leading to the cancellation of these rounds. “Regarding the auction of the remaining 120 blocks out of the 204 cancelled coal mines, the timeline for the allocation is under consideration by the Ministry of Coal,” Susheel Kumar, coal secretary, had stated in an interview with Power Line last year.

The need for more coal mines to be allocated/auctioned beyond the current pipeline is also open to question. According to the KPMG report, “The total capacity of mines allocated/auctioned (including to CIL, Singareni Collieries Company Limited [SCCL] and Northern Coalfields Limited) as on date is about 1,500 mtpa at the current rated capacity. In view of the likely demand (base case scenario), there is limited requirement of starting new coal mines, except the ones already auctioned/allocated.”

So, while the government revisits the question of whether more captive coal block auctions are required or not, and which methodology should be followed, there are many immediate challenges that it needs to tackle. The primary among these is getting the already auctioned/allocated blocks operationalised as soon as possible as significant investments are locked in. There are a number of lingering legal and regulatory concerns pertaining to the allocated blocks. These include the capping of fixed charges. Reportedly, a committee headed by the cabinet secretary and including the secretaries of the power, coal, steel and other ministries has been formed to look into the reasons for the low production from the captive coal blocks.

In sum, the coal market has seen a paradigm change in availability over the years, from shortages to surpluses, cancellation of captive coal block allocations, move to e-auctions, introduction of auctioning of linkages and now, allowing the entry of private players in commercial mining. Whether the latest move will be a success remains to be seen.