The United Nations’ top climate body, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), recently released the second report of its sixth assessment, known as AR6. The report follows the first one, published in August 2021, which was focused on the science of climate change. The current one, released in February 2022, focuses on assessing climate change impact through the lens of human communities, biodiversity and ecosystems at global as well as regional levels. A third report, expected later in 2022, will focus on policy actions around climate mitigation and adaptation.

Building on the work of its previous reports, the IPCC’s new report was worked on by over 200 authors. One of the key messages from the report is that the extent and magnitude of climate change impact are larger than estimated in previous assessments. “The report is a dire warning about the consequences of inaction,” IPCC chairman Hoesung Lee stated at the launch of the report.

The IPCC (which is an intergovernmental body of the United Nations, composed of scientists and other expert volunteers) carries out assessment reports, or reviews of the latest research on climate science, every six or seven years on behalf of governments. The first assessment report was published in 1990, while the fifth one was published in 2014.

A quick look at some of the key takeaways from the newly released IPCC report…

Climate resilient development

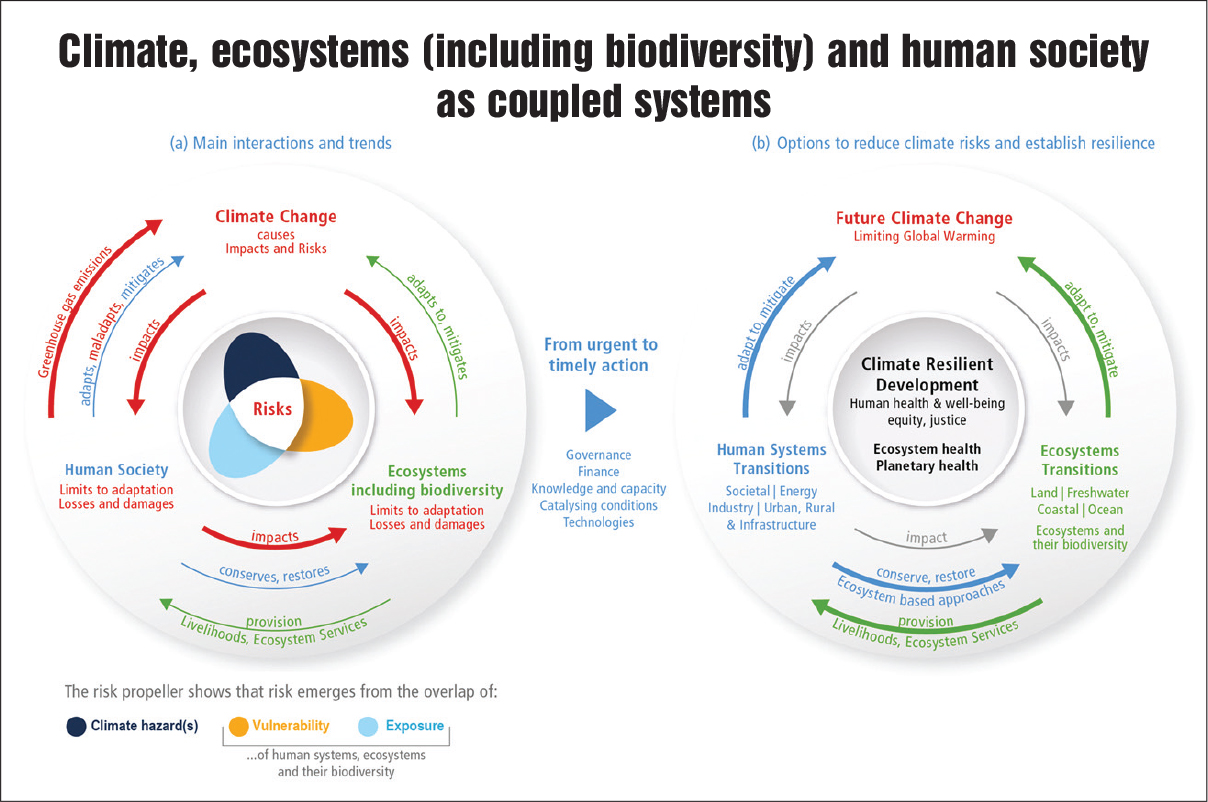

The report focuses on climate-resilient development, highlighting the fact that the prospects for climate-resilient development will be limited if the global warming level exceeds 1.5°C and may be impossible in some regions and sub-regions if the global warming level exceeds 2°C. This is because climate-resilient development is most constrained in regions where climate impacts and risks are already advanced, including low-lying coastal cities and settlements, mountains, small islands, deserts and polar regions.

In addition to this, regions with high levels of poverty, vulnerable urban environments, water, food, and energy insecurity, degraded ecosystems, etc. face several non-climate challenges inhibiting climate-resilient development, which are further exacerbated by climate change.

The report also finds that urban systems are critical, interconnected sites for enabling climate-resilient development, especially at the coast. Hence, coastal cities and settlements play a key role in moving toward greater climate-resilient development. Further, inclusive governance, as well as investment plans aligned with climate-resilient development, are key factors for enabling climate-resilient development.

As per IPCC estimates, climate change over the next decade is expected to drive over 32-132 million more people into extreme poverty. Moreover, an additional 350 million people are expected to experience water scarcity by 2030, and as much as 14 per cent of terrestrial species will face high risks of extinction. The IPCC projects that by the year 2030, extreme droughts across the Amazon will spur rural migration to cities, forcing people to live on the margins. Climate-resilient development not only integrates adaptation measures with mitigation strategies for advancing sustainable development, but it also deals with questions of equity and system transitions in land, ocean and ecosystems; urban and infrastructure; energy; industry and other societal aspects. As per the IPCC report, opportunities for climate-resilient development in various regions and subregions are not equitably distributed. Climate impacts and risks exacerbate vulnerability as well as social and economic inequities, thereby increasing developmental challenges. This will lead to undermining efforts to achieve sustainable development, particularly for vulnerable and marginalised communities. Therefore, effective and equitable adaptation and mitigation in development planning can reduce vulnerability, conserve and restore ecosystems, and enable climate-resilient development.

Current adaptation scenario

Current adaptation scenario

Ecosystem-based adaptation approach: As per the report, the ecosystem-based adaptation approach for tackling climate-induced roadblocks encompasses a wide range of strategies, from the protection, restoration and sustainable management of ecosystems to more sustainable agricultural practices such as integration of trees into farms, planting trees in pastures, and an increase in crop diversity. This approach has the potential to reduce the climate risks that many people already face, while also delivering co-benefits for biodiversity, livelihoods, health, food security and carbon sequestration.

Social programmes for equity and justice: Social programmes that improve equity and justice can lower the vulnerability of urban and rural communities to a wide range of climate risks. These measures are more effective when coupled with efforts to improve access to infrastructure and basic services. Furthermore, partnerships between governments, civil society organisations and private players can ensure the provision of crucial services for building climate-resilient communities.

Adaptation finance: Although financial constraints are key determinants of soft limits on adaptation across sectors and regions, current global financial flows for adaptation are insufficient, constraining the implementation of adaptation options in developing countries. Moreover, adaptation finance has come predominantly from public sources, while adverse climate impacts can reduce the availability of financial resources by incurring losses and damages, and impeding national economic growth, leading to an increase in financial constraints for adaptation, particularly for developing and least developed countries.

The IPCC finds that efforts today are still largely incremental, small-scale and reactive, with most focusing on current impacts or near-term risks. In addition to this, emerging evidence suggests that coupling nature-based solutions with engineered options such as flood control channels may help reduce water-re-lated and coastal risks. Although access to better technologies can also help strengthen resilience, some climate adaptation responses can have a detrimental impact due to poor design or implementation.

Impacts, risks and decision making

In order to avoid climate risk, there is need for urgent action and decision-making by way of retrofitting existing urban design, infrastructure and land use.

Equitable partnerships

Taking into consideration various aspects of socioeconomic circumstances, adaptation and sustainable development actions will provide multiple benefits, particularly to national governments, non-governmental organisations and international agencies working across sectors in partnerships with local communities and providing constant support. Equitable partnerships between key stakeholders can advance climate-resilient development by addressing structural inequalities, cross-city risks, insufficient financial resources, and the integration of indigenous and local knowledge. Numerous agroecological principles and practices, ecosystem-based management in fisheries and aquaculture, and other approaches that work with natural processes support food security, nutrition, health and well-being, livelihoods and biodiversity, sustainability, and ecosystem services.

Sustainability across food systems

To reduce climate risk while increasing sustainability in food systems, effective adaptation options coupled with supportive public policies can play a major role. It is important to understand that institutional feasibility, the adaptation limits of crops, and cost-effectiveness can also influence the effectiveness of adaptation options. Moreover, there are various trade-offs and barriers associated with such approaches. These include the costs of establishment, new knowledge, access to inputs and viable markets, etc., with their potential effectiveness varying substantially in terms of socio-economic context, ecosystem zones, species combinations and institutional support. So, to enhance food security and nutrition, integrated, multi-sectoral solutions, addressing social inequities, and differentiating responses based on climate risk and the local situation can change the game.

The report concludes that recognising climate risks early can go a long way in strengthening of adaptation and mitigation actions, as well as loss and risk reduction. This can be done through appropriate governance, finance, knowledge and capacity building, technology, and favourable conditions. As per the report, urban climate-resilient development has been observed to be more effective if it is responsive to regional and local land use development and adaptation gaps, and addresses the underlying drivers of vulnerability. By prioritising finance to reduce climate risk for low-income and marginalised residents, including people living in informal settlements, a lot can be gained in terms of well-being.